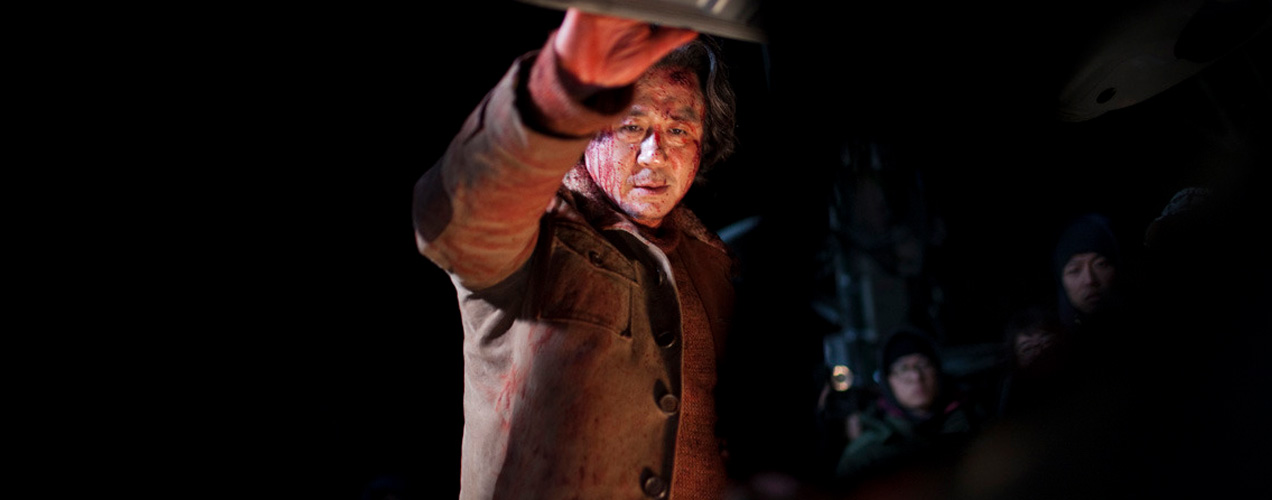

2010 / Kim Ji-woon > Kim has defined himself as one of the most versatile mainstream directors in Korean cinema. With outings that include the very good neo-noir in A Bittersweet Life, a Western steampunk epic in The Good, the Bad and the Weird and his foray into the English language with Last Stand later this year, it’s little surprise he was able to secure two of Korea’s top actors for I Saw the Devil: Lee Byun-hun (who many in the U.S. know as Brian Lee a.k.a. Storm Shadow in G.I. Joe) and Min Sik-choi (who, known widely in the West for his role as Oldboy, makes a long-awaited return to the big screen).

There’s no smoke screen here: I Saw the Devil is about vengeance in the best way possible. Or is it the worst? That may, in fact, be the central question at bay. In his quest to avenge his wife’s death, a government agent falls so deep down the rabbit hole that we’re asked to second-guess how far we’d go to satisfy our deepest desires for revenge. But the lessons here aren’t anything extraordinary. We walk away feeling mildly disgusted with ourselves not because of the gruesome violence we’ve been exposed to, but because it didn’t mean much. Had this been made by a lesser filmmaker with lesser actors, it would have been naturally panned. But Kim, at the very least, knows how to direct an entertaining thriller that plays out with few visible regards for a moral compass. And though he’s slightly late to the game—the genre has become so saturated over the last decade that the film’s twists become relatively predictable—the film still works as a misdirection from our daily lives where we’re expected a greater level of human compassion.