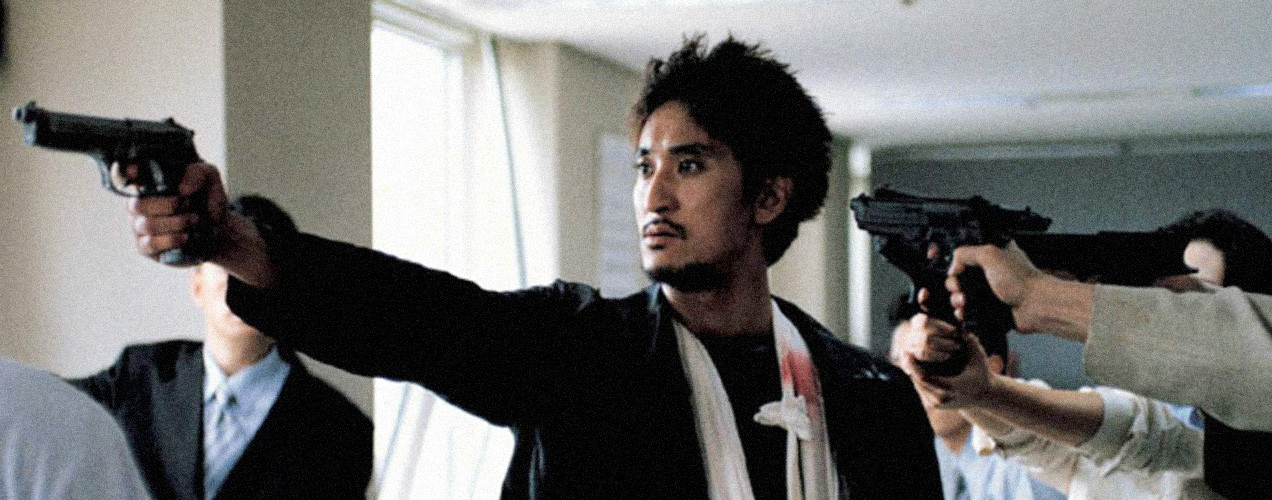

2001 / Jang Jin > A powerhouse cast (including The Man from Nowhere’s Won Bin and Sympathy for Mr. Vengeance’s Shin Ha-kyun) depict a quartet of assassins who are more of a dysfunctional family than a professional troupe. Jang’s direction results in a light-hearted, though poignant, black comedy: Amidst killings and a detective on their tail, they love and enjoy the little things in life. Guns & Talks was a relatively big hit in Korea, but unfortunately came out before Korean cinema really took off in the West. There are genuine laughs here that are in dire need of greater appreciation.

Category Archives: 4.0

Beijing Blues

2012 / Gao Qunshu > Beijing vs. Shanghai is always a fascinating study. It’s as if the higher ups in the government decided to draw a line between fun and no fun, between smiling and being a square, between the West and the East. And no matter how adventurous the barrage of insects on a stick outside Tiananmen Square is compared to The Bund, Beijing still comes off as the cold, bitter and smoggy brother of its brethren.

2012 / Gao Qunshu > Beijing vs. Shanghai is always a fascinating study. It’s as if the higher ups in the government decided to draw a line between fun and no fun, between smiling and being a square, between the West and the East. And no matter how adventurous the barrage of insects on a stick outside Tiananmen Square is compared to The Bund, Beijing still comes off as the cold, bitter and smoggy brother of its brethren.

Maybe that’s why Beijing Blues is so incising: the city that holds itself like a cold, locked down safe is cut in half. It shows its weaknesses through the eyes of a police captain like anyone and everyone. Sure, he has a certain conviction to do good, but that doesn’t keep him from telling his wife to stay in the kitchen. That’s not surprising, though: People excel in some areas and are weak in others, balancing out their humanness. And Beijing is, regardless of the attempts by its government superiors, a city of such humans.

Beijing Blues is a character study, both of the police captain Zhang as well as the city in question. In their humanity, there are details of self-preservation instilled: certain thieves, for example, only chase after non-Beijingers. And justice, it is said, should not come at the expense of breaking the law. The film undfolds as a police procedural though without the glamour of Johnnie To’s crime epics. Mood-wise, it’s hard to pinpoint it as a comedy or drama as some scenes are just plain ridiculous. Then again, a city as big as Beijing surely has such moments. With its near-sterile, calculative approach to storytelling, one could argue that this is a Jia Zhangke film with cops and robbers. It could even be dubbed an “action contemplative” film filled with long shots of the capital’s streets against the backdrop of local pop music, including a particularly gorgeous scene where Zhang is followed through the night by a man of mystery. Why is he chasing Zhang? He’s not violent, but he’s obsessive. It’s one of the film’s small mysteries that gets answered at just the right time.

Unique to the film is the cast list: When the credits roll, not only do we find out the names of the actors, but also their real-life professions. Our police captain is played by Zhang Lixian, a “well-known publisher.” Others include “a security guard in Shuangyushu Police Station in Beijing,” a “well-known TV presenter” and a “director and playwright of experimental modern drama.” In short, a cast of non-professionals filling out the roles of characters in the city they inhabit. Is this simply a love letter to Beijing? Maybe, but one thing’s for sure: Its victory at Taiwan’s Golden Horse Awards for Best Picture was both shocking and impressive. Though one would hope Beijing Blues was rewarded for its filmmaking, there’s undoubtedly a foundation of respect for getting the mainland capital to tear down its facade, showing its people to be like you and me, getting its humanity out in the open.

Lolita

1962 / Stanley Kubrick > Say what you want about the Hays Code, but Lolita is a clear example of where it worked wonders: Kubrick was forced to adapt Nabokov’s classic for the screen with a level of creative subtlety that allowed its sexual proclivity to be hidden in plain sight. As the word “Lolita” itself has become part of our everyday vocabulary, it’s now nearly impossible to go into the film with any expectation of shock. Thus the film not doling around on the erotic and, instead, focusing on the madman-at-hand actually benefits the storytelling. Admittedly, it lacks the in-depth analysis of Humbert Humbert, played so tautly by James Mason, but what it leaves to our imagination is much more preferable. We’re allowed to fill in the gaps of what kind of background forces upon an older man the preference of younger, so-called “nymphettes” instead of women of similar age.

Unlike the novel, which is written from the viewpoint of a highly unreliable, subjective narrator, the film takes a couple of steps back but still keeps us within arms’ reach of the situation. Across from Mason, 16-year-old Sue Lyon’s performance as the titular character is astounding in its sophistication. It’s hard not to wonder if she’s an older actress playing the part of the 14-year-old, but such is the effectiveness of her “range” that has the feel of anywhere from 13 to 25. All the while, there’s something very contained in her sensibilities that makes us wonder how much of what we perceive in the film is morally apt. Nabokov was considerably more black and white about Humbert’s nature of obsession, but Kubrick’s not nearly as judgmental. And the film is better for it—even with Dr. Strangelove’s forceful and unnecessary cameo.

Margin Call

2011 / J.C. Chandor > Actual Bloomberg terminals and financial terminology without explanations: Have we come this far in cinema? Can we actually approach Wall Street without caricaturing it? Chandor’s one-night-before-the-crisis take of a fictional Bear Stearns-wannabe is a giant step in filmmaking. Finally, we have a thoughtful, deliberate film about the crisis without condescension or a moral high-ground. Amidst the cries of crowds at Occupy Wherever, we are charmed with a thriller that allows us to track the moment of discovery to the impending fallout, all while focusing on the humanity of the situation. It doesn’t matter whether one is a socialist or a capitalist, the reality is that truth often gets pounded by hearsay as long as it serves a greater purpose. But every story has two sides, and Margin Call does its damnedest to tell both. Were it not for the gravely miscast Demi Moore and slightly heavy expository dialogue, this could really have been one for the books. Still, the film is a must-see for anyone trying to dig into the psyche of those who stood at the foundation of a crisis that some will never forgive.

M

M by Fritz Lang is the yearly favorite from 1931 as listed in Life as Fiction (Through Time): An Exercise in the Clockwork and Constriction of Cinematic History, a project to chronicle my favorite film from each year since 1921.

1931 / Fritz Lang > How does M hold up to the test of time over similar cinema of the past (and recent times) that eventually fade from memory? Unlike others in the genre which have lost their luster due to overused plot twists, a simple sense of age or technical awkwardness, M stands firm because Lang’s filming is claustrophobic but not overdone. His storytelling is imaginative but coherent. His treatment of the villain is respectful but not apologetic. In fact, it still supersedes most of its successors in terms of intelligence and overall composition.

Nowadays, tension in serial killer films seem necessary to be represented throughout the running time. However, in M, the great beauty is in its objectivity. The serial killer himself—and his capture—is only part of the game. The cops and robbers, the bystanders and victims, they all play a part in the total landscape without overshadowing the other. Moreover, it’s impossible not to see what it’s influenced (most notably, in my mind, was Sympathy for Lady Vengeance). Increasingly, this is one of the few classics where a modern remake would be interesting just to see if 80 years of technology and know-how could actually trump the original.

Originally posted on July 10, 2007 before inclusion into (Through Time).

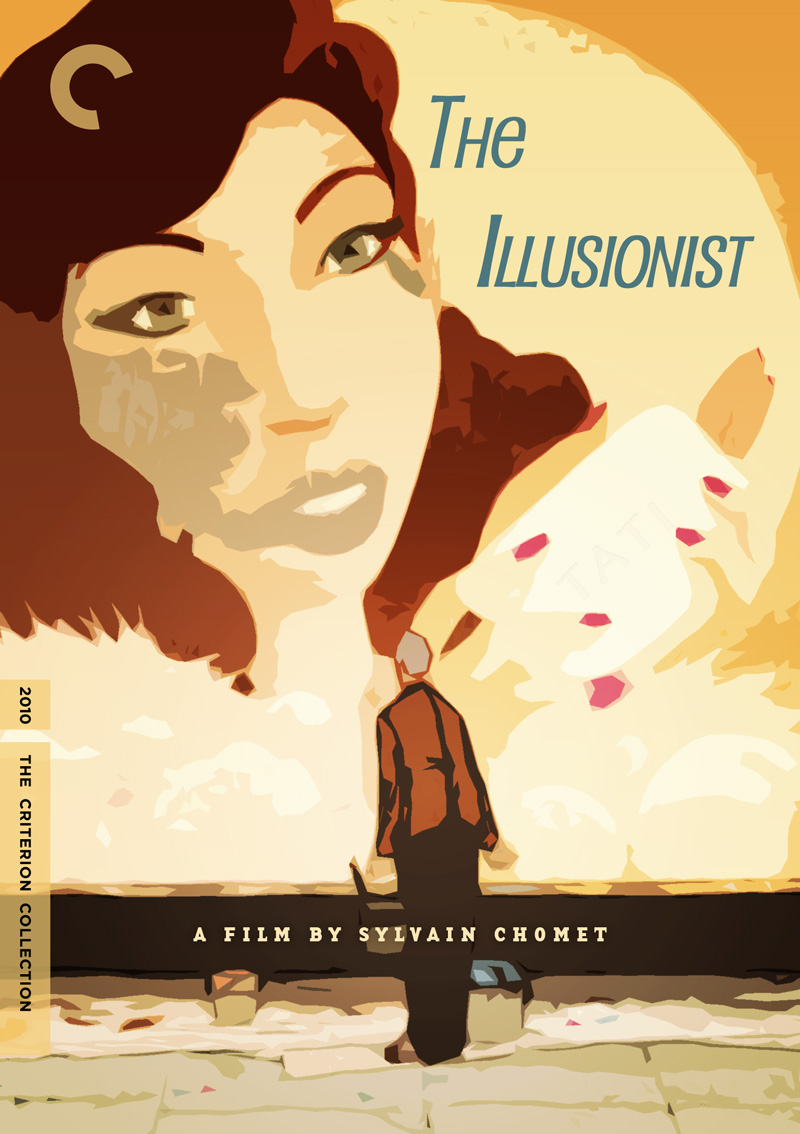

The Illusionist

#3: The Illusionist by Sylvain Chomet. In the ten days leading up to the 83rd Annual Academy Awards, I listed my ten favorite films of 2010, each accompanied by a custom Criterion Collection cover inspired by Sam Smith’s Top 10 of 2010 Poster Project.

2010 / Sylvain Chomet > Charming. Heartbreaking. Wonderful. Chomet’s follow-up to the brilliant The Triplets of Belleville isn’t nearly as clever, but its story of lament and regret is equally as powerful. Originally written by iconic French filmmaker Jacques Tati in an attempt to reconciliate with an estranged daughter, L’illusionniste captures the kind of magic that cinema was always intended for. With almost no dialogue, Chomet is able to tug at our heartstrings with gorgeous, hand-drawn animation that transports us to a very different time and place. This isn’t earth-shattering stuff, but there’s something delightful in accompanying our magician in his twilight as he inadvertently becomes the guardian of a naive, young girl. His little tricks make us smile, but his inability to connect with the girl at a deeper level instills in us a tragic sense of eventuality. By not being explicit about their motivations, Chomet allows us approach the film how we choose. At a sparse 80 minutes, every scene is essential and none are heavy-hearted. Its beauty is in its simplicity, and it may be best watched on an overcast day as rain trickles down.

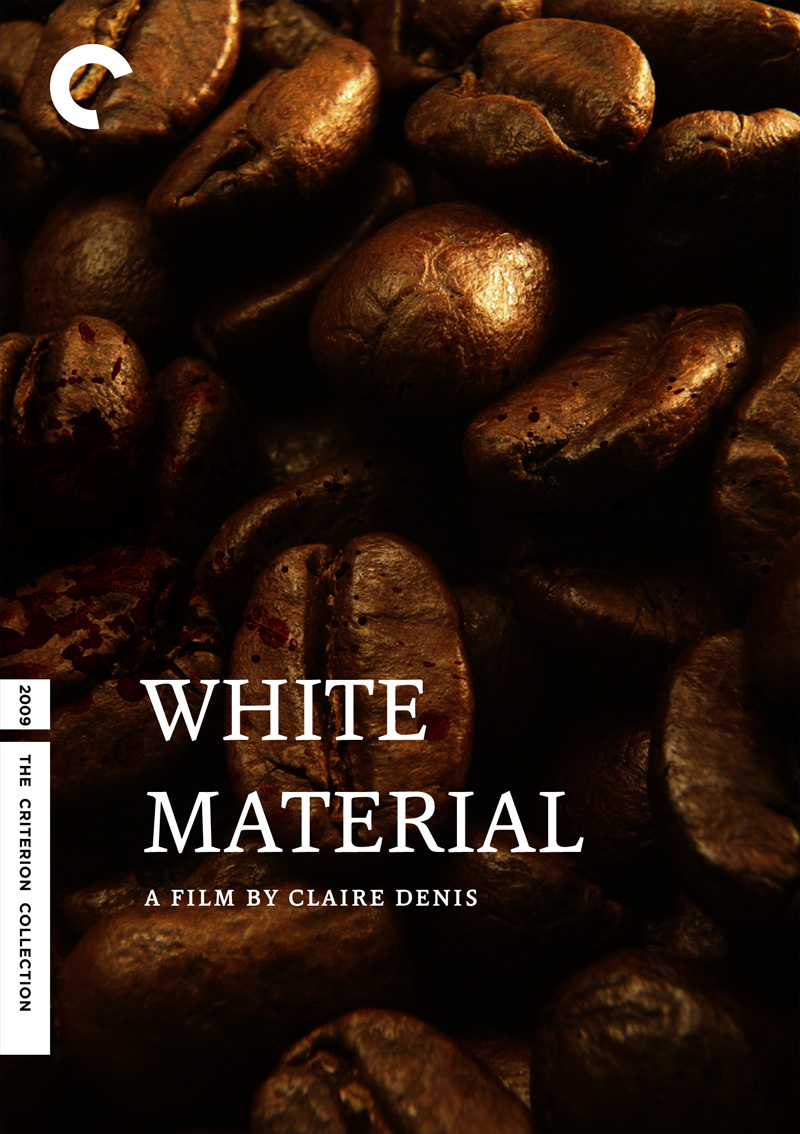

White Material

#4: White Material by Claire Denis. In the ten days leading up to the 83rd Annual Academy Awards, I listed my ten favorite films of 2010, each accompanied by a custom Criterion Collection cover inspired by Sam Smith’s Top 10 of 2010 Poster Project.

2009 / Claire Denis > Cinema has rarely treated colonialism with an objective eye. Instant disdain has been nothing short of what’s been expected in a society hellbent on correcting wrongs of the past by hurting the present and future. Everything from affirmative action in the United States to the black empowerment movement in South Africa has set us up for further clashes without actually understanding the roots of the troubles. Even the origins of something as ever-present as Islamic terrorism remain oblivious to much of society, but you can’t always blame them for it. The job of the mass media is to enrich and educate the lives of those who come home from a hard day’s work, but sensationalism has taken precedence in lieu of rational discourse.

So, where do we go from here? While PBS may be on its last legs, technological ease has paved the way for well-spirited blogs and open-minded films like White Material. Unlike the foundation of liberal guilt that pervaded Hotel Rwanda, Denis makes no apologies for what the white man has done to Africa. She accepts it as fact, but digs deeper into the mindset of those who stay behind when the proverbial revolution happens. How does one treat those who were born into colonial society? Do we look with contempt the second or third-generation offspring who’ve always considered the African soil their home?

White Material is rich with doubt: Will there be a tomorrow? Will we survive even if there is? Will we be wanted? It is Denis’ elegy to colonialism and represents the darkest corners of The African Queen. Isabelle Huppert is magnificent as Maria Vial, a woman trying to keep her coffee plantation functioning while the world around her falls apart. The enemies are both within and without, with additional tension provided by Maria’s disillusioned son (played by Nicolas Duvauchelle in one of the best supporting performances of 2010). This is a film that promotes understanding of a dying world, one that we’ve already been told is very, very bad. But not all people, even when part of a terrible injustice, are evil. Sometimes circumstance just kills.

The Social Network

#5: The Social Network by David Fincher. In the ten days leading up to the 83rd Annual Academy Awards, I listed my ten favorite films of 2010, each accompanied by a custom Criterion Collection cover inspired by Sam Smith’s Top 10 of 2010 Poster Project.

2010 / David Fincher > Everything’s been said about Fincher’s take on Mark Zuckerberg and the birth of Facebook. Ambition, betrayal, Aaron Sorkin’s biting dialogue—all these add to 8 Oscar nominations and near-universal acclaim. But sadly, The Social Network may be one of those films that feel so “important” that it’s hard for any self-conscious viewer to admit in disliking it. It’s technically sound filmmaking that lacks the heart which might propel The King’s Speech to Best Picture. It’s a film for those who thrive on competition and know, because of that drive, how easy it is to lose family and friends. It describes a culture all too common in upper academia of the northeast and Silicon Valley, where intelligence and wealth intersect in devastating fashion.

Jesse Eisenberg’s Zuckerberg is cold, defensive. But what makes his Best Actor nomination worthy is the the vulnerability he shows throughout. It’s amazing, in fact, how much one’s insecurities actually work as a motivator. Whether the story’s true or accurate doesn’t actually matter, though. This is a movie; it’s effectively fiction. And for that, Eisenberg, Andrew Garfield and Armie Hammer brilliantly bring to life the game’s players with unique characteristics, often built on Sorkin’s snarky writing. The much-lauded screenplay isn’t perfect by any means. People don’t talk in such witty quips, but thankfully Sorkin left out much of his liberal slant—there’s a different kind of politics at play here.

Unusually, The Social Network works as a motivator as much as Rudy or Breaking Away. You watch these guys battle it out and wonder if you could have done the same. Maybe not everyone goes to an Ivy league school, but everyone has ideas. And it doesn’t matter if you’re in a small town in the corner of Idaho or at Harvard Square, these ideas can be put to work. The Internet has made anyone’s ambition possible. And suddenly, in some way, in Zuckerberg, there’s a bullseye to target.

Blue Valentine

#6: Blue Valentine by Derek Cianfrance. In the ten days leading up to the 83rd Annual Academy Awards, I listed my ten favorite films of 2010, each accompanied by a custom Criterion Collection cover inspired by Sam Smith’s Top 10 of 2010 Poster Project.

2010 / Derek Cianfrance > A brutally honest dissection of a crumbling marriage. Young love, in and out of love. The process is painful, but what sets Blue Valentine apart from a pityfest is Cianfrance’s ability to conjure the magical moments that made all the pain worth it. The cynic in me argues that romance is an ideal brought forth by the media for capitalist gain. But that’s just silly: We all want to be loved, but it just so happens that we don’t always know the best way to be loved. It’s become a game of politics in the modern-age, driven at its core by the free flow of information and ease of physical travel: Twenty years ago, it was much harder to cheat on your husband. Now you can flirt all day as SxyGrl23 on a multitude of adult dating sites. And if someone catches your eye, Southwest Airlines will help you get away.

Boredom punishes us and jealousy weakens our dedication. That’s why relationships are hard work. That’s why we should cheer for those who don’t give up.

The film is founded on the incredible performances of Michelle Williams and Ryan Gosling. The latter, by my count, is the best I’ve seen from 2010—though the Academy was quick to ignore him completely. They carry every scene with such raw beauty that it’s hard not to believe in every simple act. Nobody’s a villain. Everyone has their reasons, no matter how opaque. The brilliance of the script is its inability to judge people for being human. In fact, not since 2006’s Flannel Pajamas have we experienced such objective adoration for the act of romance and its subsequent disenchantment. Alas, if there’s another reason to cheer, it’s that Blue Valentine and Winter’s Bone have given us proof that independent cinema without pretension is alive and well in America.

Mr. Nobody

#7: Mr. Nobody by Jaco Van Dormael. In the ten days leading up to the 83rd Annual Academy Awards, I listed my ten favorite films of 2010, each accompanied by a custom Criterion Collection cover inspired by Sam Smith’s Top 10 of 2010 Poster Project.

2009 / Jaco Van Dormael > In the words of Lauryn Hill: “Everything is everything.” That may be Van Dormael’s message in Mr. Nobody, an ultracomprehensive look at living, decision-making and learning not to worry about the consequences. It can be argued that even on our deathbeds, we may not have the perspective to know if we’ve made an impact upon this world. But ultimately, our own happiness at the moment our eyes close may dictate how successful we’ve been. But while we’re on this earth, it’s impossible for our wandering minds not to second-guess our every decision. Fear not, however, as thanks to an angelic mishap, Nemo Nobody has a gift: He can live every life of every alternate universe that has ever been possible. And in our journey with him, we learn that the good can be bad, vice versa, and if anything, making the best of what you’ve got is really the only way to go.

Cinematically, Mr. Nobody is joy. Van Dormael’s passion and energy is embodied in every sequence, keeping us guessing, excited and caring. At the center, Jared Leto’s adult Nobody is an intriguing figure who we can’t ever pinpoint because, frankly, we’re not always sure which of his decisions we’re following. But none fascinates more than the younger Nemo, played by Toby Regbo (who’s soon-to-be the young Dumbledore in the second in installment of Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows). His onscreen chemistry with Juno Temple evokes in the viewer a romanticized nostalgia about first loves. The strength of this carries itself throughout the film until it culminates in the purest of ways.

Always visually charming, Mr. Nobody is an emotional epic that’s somehow failed to get U.S. distribution despite having brand name actors and superb (at a nearly $50mn budget) production quality. While it may be a conceptual film at its core, unlike forced-puzzles like The Prestige where it’s more of a chore to connect the dots, there’s actual human satisfaction in discovering Nemo Nobody’s secrets. After all, the rationale for the film’s discordant structure is based on our own realities.