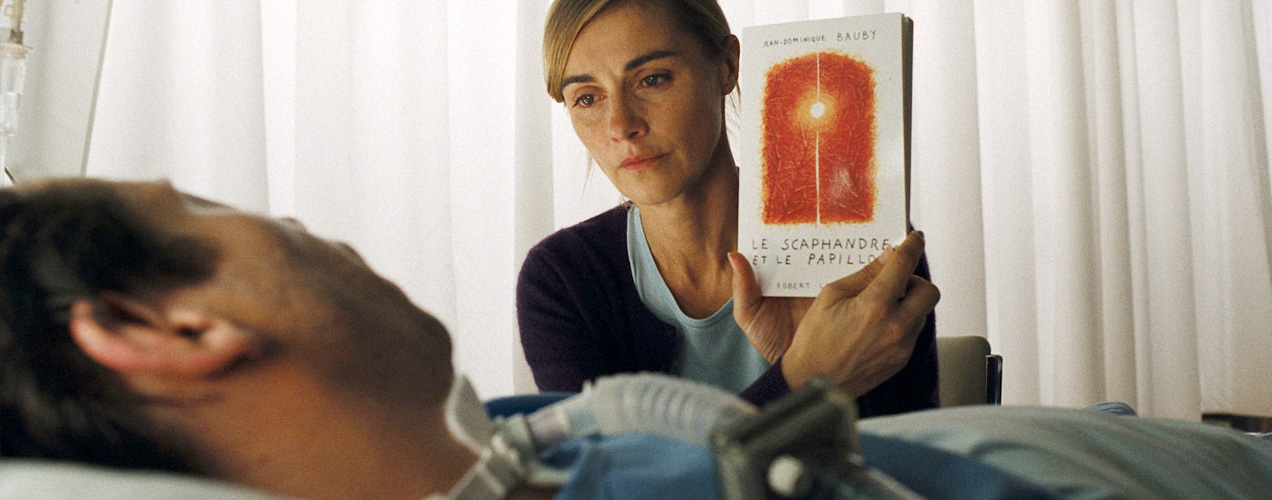

2007 / Julian Schnabel > When I first heard this was going to be made into a film, I was filled with both worry and wonder. A film about a man who communicates by blinking? How interesting could that be on the screen? In amazement and awe, however, Schnabel and cinematographer Janusz Kaminski (who ought to be a lock for an Oscar nod) have adapted The Diving Bell and the Butterfly into celluloid with a level of imagination that even Jean-Dominique Bauby may not have had in his writing process. The scenes where Bauby (played immaculately by Mathieu Amalric) and his father (played by an appropriately aging Max von Sydow) communicate before and after the stroke are mesmerizing and heartbreaking. All the women in the film shine in reflection to Bauby’s “butterfly,” each adding an extra layer of emotion and character to a life not to be pitied. No doubt one of the year’s very best, the film is an epic of human creativity and strength.

Category Archives: 4.5

Be with Me

2005 / Eric Khoo > Be with Me is structurally flawed. On a pure fundamental basis, the trio of stories that create the network within the film should each have a similar level of importance and screentime to keep the balance, right? Khoo decides otherwise and starts to increase the focus on a specific one as the film progresses, weaving in a documentary style because, as we find out, one of the characters is actually a real person—Theresa Chan, the Singapore equivalent of “Helen Keller.” This mismatch of fact and fiction is jarring to us because we don’t know whether to take this as entertainment or a life lesson.

The film’s style, with a total of 2.5 minutes of dialogue in its ninety-three minute span, is sparse but elegant. Each shot is gorgeous in its own right, and the transitions are apt and don’t reek of style over substance. The unfolding of each story is judiciously spliced and paced to keep enticing us. The real meat, once it gets rolling into its third and final act, is its open-ended theory on love and loneliness. It’s a thesis of sorts in understanding the have and have-nots, and its true beauty is in the manner in which it translates this fiction into a real-life perspective. It’s heartwarming but strong, quaint and unforgettable.

Pan’s Labyrinth

2006 / Guillermo del Toro > The combination of fantasy and violence is something that’s always fascinated me because at the core of most fairy tales is a sense of naivety that is both wondrous and disagreeable. Emotions toward the latter comes outward mostly because we realize that stories are an escape, and that fairy tales don’t really happen without hard work (i.e., don’t exist). In film, we simply take a ride in our minds that comes hurling back to square one once the end credits roll.

With Pan’s Labyrinth, del Toro has given respect to the reality of time and space while still proceeding with his story of magic. The parallelism of good vs. evil along with the convex nature of Ofelia’s fate are the cornerstones of the film’s effectiveness. And since the idea of the happy ending is a modern one (and not one that’s fair or objective to the viewer’s emotions), I believe del Toro’s choice of conclusion judiciously stops short of manipulating the viewer and the viewer’s after-film hopes.

I’m neither perturbed nor surprised that The Lives of Others beat out Pan’s Labyrinth for the Oscar for Best Foreign Language Film. Both are beautifully crafted, but the latter’s taste in violence is not fit for all. That being said, only The Last King of Scotland and Memories of Matsuko compete with this as my personal favorite films of 2006.

A Good Lawyer’s Wife

2003 / Im Sang-soo > There are so many layers to Im’s A Good Lawyer’s Wife that a minimum of two viewings are a must. But even on the first viewing, it’s fairly evident that he’s created a fine work exploring the status of the modern Korean family, analyzing issues with aging, infidelity, class distinction, adoption and love/loneliness. It’s easy to imagine a sophomore film class dissecting the ground beneath the film for a week, pondering exactly what Im intended to say, and what is just a natural consequence of the world he’s trying to represent.

Much of this, undoubtedly, is driven by the incredible cast. Of note, as always, is the sheer blistering performance, subtle and true, of Moon So-ri in her portrayal of the title character (for which she won Best Actress at the 2004 Grand Bell Awards). Moreover, I found the film to have some of the most successfully interesting use of music I’ve ever witnessed: A mixture of upbeat orchestration and mismatched visuals often bringing forth feelings that would generally be hidden away.

I could go on, but it’s probably better to just watch it. The combination of Im Sang-soo and Moon So-ri yields a result that ranks atop the ten best Korean films produced this decade, and establishes Im as a cornerstone director of contemporary Korean cinema.

Half Nelson

2006 / Ryan Fleck > Bad before the good: Much of the film’s realism and objectivity is lost through the “mini-lectures” made on society and the government. While interesting, they take away from the interplay between the king (Gosling) and queen (Epps) of the show. The only reasonable explanation for these inserts might be that writers Fleck and Anna Boden needed a little bit of this and that to stretch the original short (“Gowanus, Brooklyn”) into this full-fledged feature.

That aside, the poignancy of Half Nelson is present in the way it’s resonated in my mind for the past few weeks. Against the backdrop of Broken Social Scene’s score, Gosling’s portrayal of a crack-addicted schoolteacher in the inner-city is a testing experience. The beats are heavy, and the film is filled with areas of gray that have little in terms of definition. Shareeka Epps’ performance as Gosling’s headstrong pupil is glowing—undoubtedly one of the breakout young actors of the year. Not much of the story is predictable. The second half of the film crescendoes into its final sequence, one of heartbreak and simplicity. Things click, and things may or may not work. Thankfully, the film does.

The Bad Sleep Well

1960 / Akira Kurosawa > It’s taken me quite a while to appreciate the power of Kurosawa’s storytelling, but The Bad Sleep Well is one step closer to the nail on that coffin. Forget the fact that this is a Shakespearean adaptation (and note that knowing the story itself is of no consequence). What we have here is an elegantly crafted corporate revenge thriller that touches on multiple facets of capitalism as well as social construction. While there may be a leftist bias, thankfully the gravity of that bias is appropriate when the plot and setting are put in perspective.

Toshiro Mifune is as lean and mean as ever: No Seven Samurai-style overindulgence is necessary for him to convey his character’s anger and compassion. The remainder of the cast each flower the pot to full bloom, notably Ko Nishimura’s paranoid contract officer and Tatsuya Mihashi’s loving brother. The cryptic and often jolly musical accompaniment is haunting, and the pacing slowly builds an emotional snowball within the viewer that enhances attachment. Too often we get bored and want the bad guy to win—but here, even though at times we question the protagonist’s moral tactics, we stand by him and hope for the best.

The film is often forgotten among the annals of samurai flicks in Kurosawa’s ouevre. But The Bad Sleep Well is not simply about social relevance to today’s society, but rather a sobering experience in expert storytelling. It lacks the gimmicks that drive most of today’s films, and instead depends on human curiosity itself, an obvious yet underused technique. The wedding cake scene alone is worth the price of viewing.

Oasis

2002 / Lee Chang-dong > One of the greatest, if not arguably the most unexpected, love stories ever captured on film, Oasis is a tour de force of emotion from one of Korea’s finest directors. It’s an awkward but endearing tale of discovery between a woman with cerebral palsy and a man, fresh out of jail, who seems to be not completely there. Both Moon So-ri’s performance as the woman and Sol Kyung-gu as the man are arguably the best duo seen in Korean film in the last five years.

In direct contrast to Lee’s Peppermint Candy, which delved into the psyche of the modern Korean man, here he brings forth the universal ideal that everyone deserves to love and be loved. There are many occasions during the film where it becomes hard, even painful, to watch, but the sense of payoff is grand when the credits roll. Oasis is a true testament to the power of film.