1988 / Isao Takahata > War’s tough business, and fallout from the bloodshed affects everyone involved. Bravely and tastefully, cinema has over time tried to convey such moral dilemmas and barbaric vengeance, but once in a while, a movie comes along that makes the viewer feel dirty for the wrong reasons. Widely acclaimed for its animated portrayal of two young, Japanese orphans in World War II, Grave of the Fireflies has made me feel that way. It’s easy to justify the film’s bleak, helpless nature as a dose of realism, but I’d go as far as to say that it plays on the sensitivities of those who have dealt with wartime struggles. It manipulates the viewer without substantiating the emotions. Akiyuki Nosaka, on whose novel the film is based, was himself inspired out of sheer guilt for failing to support a family member. This guilt is what’s now being projected on the hapless viewer? That’s unfair, and the director should actually be the one to feel dirty. Our sympathy should be earned, not exploited with the tears of young children.

Category Archives: Japan

Departures

2008 / Yojiro Takita > It’s so fitting that when the Academy finally honors an Asian work with the Oscar for Best Foreign Language Film, the crown is worn by a bastion of studio-laced mediocrity. Departures reminds you over and over that you’re watching a carefully directed art film that has symbolism and emotions and all that other good stuff that separates it from the barrage of mainstream dramas. But as successful as it is in conveying the little artifacts of daily life, it’s equally as frustrating in forgetting to treat the viewer with the kind of respect necessary for this to be a mutually enjoyable experience. There’s an elegant humanist setup to the whole show that gets sideswiped in the second half by an overarching approach of connect-the-dots that has just enough edginess to garner an awards shower that’d even make the Weinsteins proud. In a year where Japan had a couple of far better films (All Around Us, Tokyo Sonata), it’s sad that the global audience will judge the market with this caricature of human development.

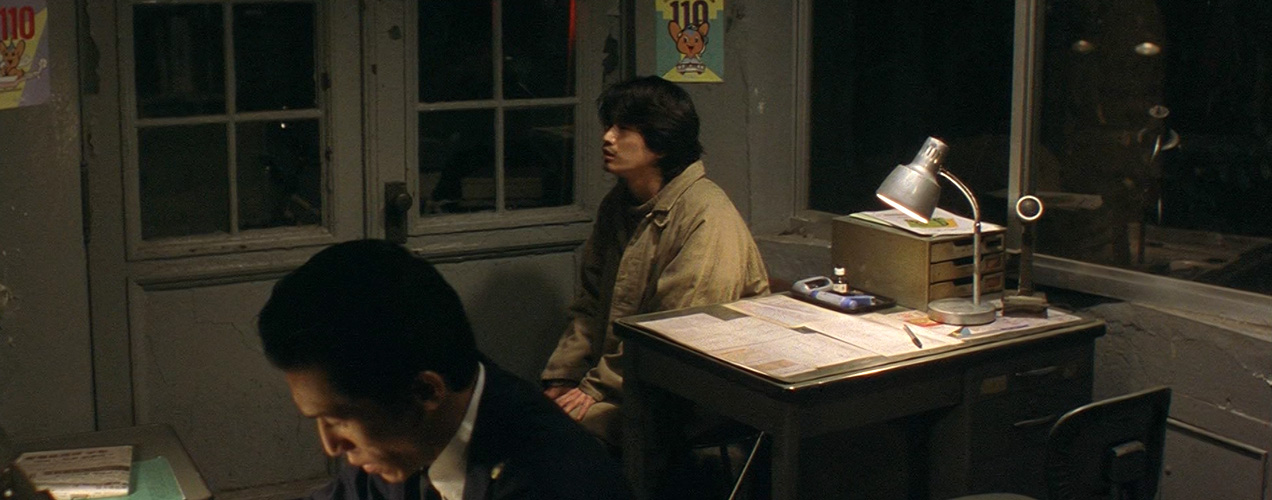

20th Century Boys 1: Beginning of the End

2008 / Yukihiko Tsutsumi > I’ve only read a handful of comics in my life, but easily one of the most fascinating (and daunting) was Naoki Urasawa’s 20th Century Boys. It spanned decades, continents and felt epic from the start. But translating such epics to the silver screen has always been an issue: More often than not, the story is altered for a new generation or the heroes and heroines are significantly miscast. Here, these are not issues. The movie stays true to the original and most of the actors seem proper enough for their roles. The big problem arises from the film’s mediocre production. For a film with one of the biggest budgets in Japanese history (around $60mn), the final product seems like it was dusted off the bargain bin. The colors are flat, lacking the glossy, refined look needed for this kind of movie and even the blood gushing scenes reek of amateur techniques. Japan, as a country, is not keen on blockbusters. When it comes to quiet, reflective cinema, it has excelled for the past decade but the mega-movie style of Hollywood continues to evade them. And it’s quite sad because 20th Century Boys should be as hyped up as Watchmen, yet the film will remain unmarketable outside Asia (and to certain manga buffs) because of its lack of polish.

2008 / Yukihiko Tsutsumi > I’ve only read a handful of comics in my life, but easily one of the most fascinating (and daunting) was Naoki Urasawa’s 20th Century Boys. It spanned decades, continents and felt epic from the start. But translating such epics to the silver screen has always been an issue: More often than not, the story is altered for a new generation or the heroes and heroines are significantly miscast. Here, these are not issues. The movie stays true to the original and most of the actors seem proper enough for their roles. The big problem arises from the film’s mediocre production. For a film with one of the biggest budgets in Japanese history (around $60mn), the final product seems like it was dusted off the bargain bin. The colors are flat, lacking the glossy, refined look needed for this kind of movie and even the blood gushing scenes reek of amateur techniques. Japan, as a country, is not keen on blockbusters. When it comes to quiet, reflective cinema, it has excelled for the past decade but the mega-movie style of Hollywood continues to evade them. And it’s quite sad because 20th Century Boys should be as hyped up as Watchmen, yet the film will remain unmarketable outside Asia (and to certain manga buffs) because of its lack of polish.

Lost in Translation

2003 / Sofia Coppola > Coppola’s sophomore effort has quite a few tangibles working for it: Impactful yet understated acting, a functional/moody location and a near-perfect mixture of ambience and rock for the soundtrack. But these only tell half of the story. The feel of it all—being alone in a city where your mind and body seems misplaced, not knowing if what tomorrow brings is worth waking up or going to bed for, wondering if the past you’ve lived is the past you’ve wanted to live—these are the intangibles that are undeniably infused into the self-analyzing experience that is Lost in Translation.

But I’d be lying if I said this was a perfect film: I find Scarlett Johansson’s character to be weak, though part of it’s because Bill Murray puts forth a subtle yet powerful performance portraying a man of such humanity that she comes off comparatively cookie-cutter. The pacing isn’t always perfect, with hiccups that seem misplaced and solo scenes of Johansson that pale in comparison to those of Murray. And while I never really found the film to be racist by any means, the xenophobic viewpoints sometimes come off silly rather than calculated. But the point remains that Coppola, with the help of Brian Reitzell and Roger J. Manning Jr.’s effusive score, has concocted a mood piece of master quality that takes away our sense of vengeful cynicism and fills it with the kind of hope and bewilderment that both the young and the young at heart seek.

Strawberry Shortcakes

2006 / Hitoshi Yazaki > As a story of four women in the anonymous city of Tokyo, Strawberry Shortcakes paces itself like life, with a steady unraveling while interjecting jolts of reality. Yazaki’s direction is meticulous and endearing, streamlining his own craft’s sensitivity to the existence of the women he’s portraying. By themselves, none of the stories are necessarily special, but rather simple slices of life with which the viewers should be able to find some sort of commonality. There are some balancing issues: For example, Akiyo the escort is a complex character and almost all her scenes yield something special for the viewer. But Chihiro, the office worker, is almost intentionally stereotypically girlish, to the point where you pity her instead of extending sympathy. Somehow, though, these balancing contradictions actually make the film more poignant with its ebbs and flows.

2006 / Hitoshi Yazaki > As a story of four women in the anonymous city of Tokyo, Strawberry Shortcakes paces itself like life, with a steady unraveling while interjecting jolts of reality. Yazaki’s direction is meticulous and endearing, streamlining his own craft’s sensitivity to the existence of the women he’s portraying. By themselves, none of the stories are necessarily special, but rather simple slices of life with which the viewers should be able to find some sort of commonality. There are some balancing issues: For example, Akiyo the escort is a complex character and almost all her scenes yield something special for the viewer. But Chihiro, the office worker, is almost intentionally stereotypically girlish, to the point where you pity her instead of extending sympathy. Somehow, though, these balancing contradictions actually make the film more poignant with its ebbs and flows.

Vexille

2007 / Fumihiko Sori > Filled with pedigree from animation legends, Vexille is one of the most astonishingly beautiful films to come out in its medium in recent memory. But as was the case with 2001’s Final Fantasy debacle, the story just can’t keep up with the visual feast. Fans of quality anime have become accustomed to plots that challenge the intellect while fusing in hardcore action. While we see loads of the latter here, only shades of the former appear in disappointment.

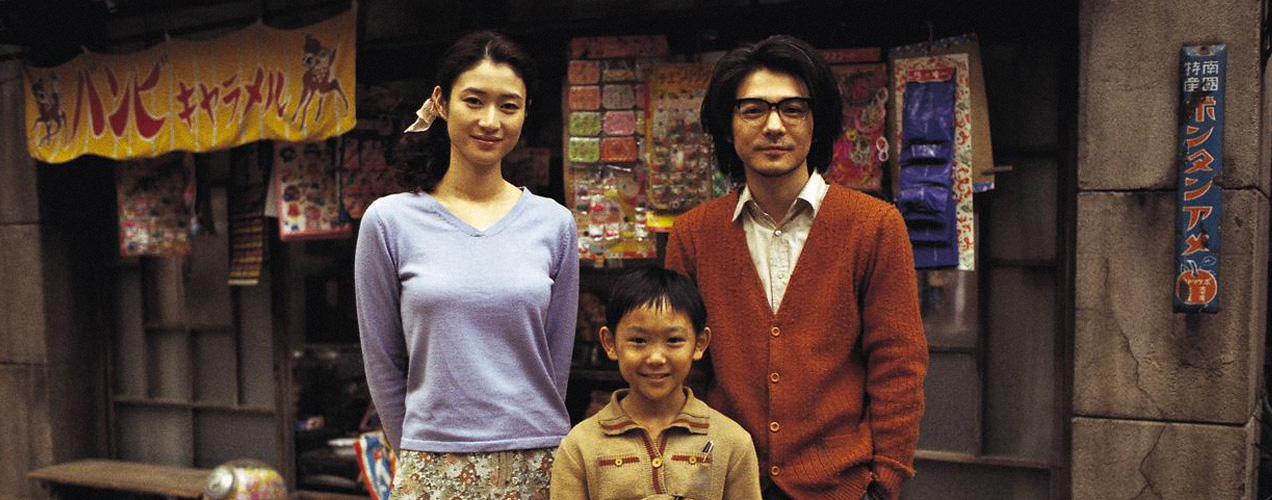

Always: Sunset on Third Street

2005 / Takashi Yamazaki > Always may have been dominant in winning 12 of the 13 major Japanese Academy Awards in 2005, but its overly sentimental tone will hold it back from being a true classic. Set in the feel-good days of post-war Japan, the film’s depiction of family life in Tokyo is charming and full of heart, but the script’s overbearing emotion tends to undermine the sublime potential the characters themselves hold. Combined with the acting (which may be the strongest suit of the film and deserving of all its awards), Always ingeniously suckers you into tearjerker moments even if you could smell the set up a mile away—pretty impressive for a sterile, heavy-handed script.

2005 / Takashi Yamazaki > Always may have been dominant in winning 12 of the 13 major Japanese Academy Awards in 2005, but its overly sentimental tone will hold it back from being a true classic. Set in the feel-good days of post-war Japan, the film’s depiction of family life in Tokyo is charming and full of heart, but the script’s overbearing emotion tends to undermine the sublime potential the characters themselves hold. Combined with the acting (which may be the strongest suit of the film and deserving of all its awards), Always ingeniously suckers you into tearjerker moments even if you could smell the set up a mile away—pretty impressive for a sterile, heavy-handed script.

Sakuran

2007 / Mika Ninagawa > Having been unable to watch more than 10 minutes of Memoirs of a Geisha, I delved into Sakuran with a level of skepticism. But Ninagawa’s depiction of oiran lifestyle is a drastic difference in mood, style and enjoyment. (Of note is that oiran are high-class courtesans while geisha are usually considered entertainers. As it turns out, the rise of geisha led to the eventual decline of oiran culture.) Taking a cue from Marie Antoinette, the film’s best attribute may be its successful mixing in of contemporary pop music within an Edo period setting. Otherwise, the pacing isn’t half-bad, and there’s something magnetic about Anna Tsuchiya’s portrayal of Kiyoha that finds one glued to the screen. The story itself isn’t particularly novel, but as it stands, it’s a fine romantic drama on its own right.

Paprika

2006 / Satoshi Kon > Maybe the shine of pseudo-existential anime is new to America, but this has been done before (notably in Ghost in the Shell and Akira, but most recently in Satoshi’s own Paranoia Agent). For all its beauty, I can’t help but think that Paprika falls short in actually showing us something new. And because of that, I also can’t really justify the complexity of the storyline and obtuseness of the conclusion. In Satoshi’s oeuvre, Tokyo Godfathers still reigns supreme in my book.

Cure

1997 / Kiyoshi Kurosawa > Visible horror is often forgettable. It’s the creepy feeling that remains after the film is over that really drives home the chills. Unfortunately, most films fail at this and end up being filled with unnecessitated gore or overtly pretentious psychological mazes. Cure, however, connects with the inner-horror of every man and woman, filling us with a sense of paranoia that may very well stay with us at days on end. What’s amazing, though, is that that feeling isn’t necessarily “evil,” as most horror would expect us to presume. It’s simply a feeling that seems almost eye-opening and surprisingly natural.