2004 / Jang Yun-hyeon > Some is a fairly intelligent mystery/sci-fi/thriller that may as well have been founded on a Philip K. Dick story, and it also shouldn’t surprise anyone that it’s written by the same woman responsible for Il Mare (later remade as The Lake House in Hollywood). The crux of the plot deals with a character having a special kind of foresight, though the film does a solid job of building around the technique so that it doesn’t become a silly gimmick. The direction is so tight that the viewer rarely gets a breather. Gone completely under the radar by many, this is a film that, while not groundbreaking, should be more voraciously consumed by those looking for twists in the action genre.

Category Archives: Korea

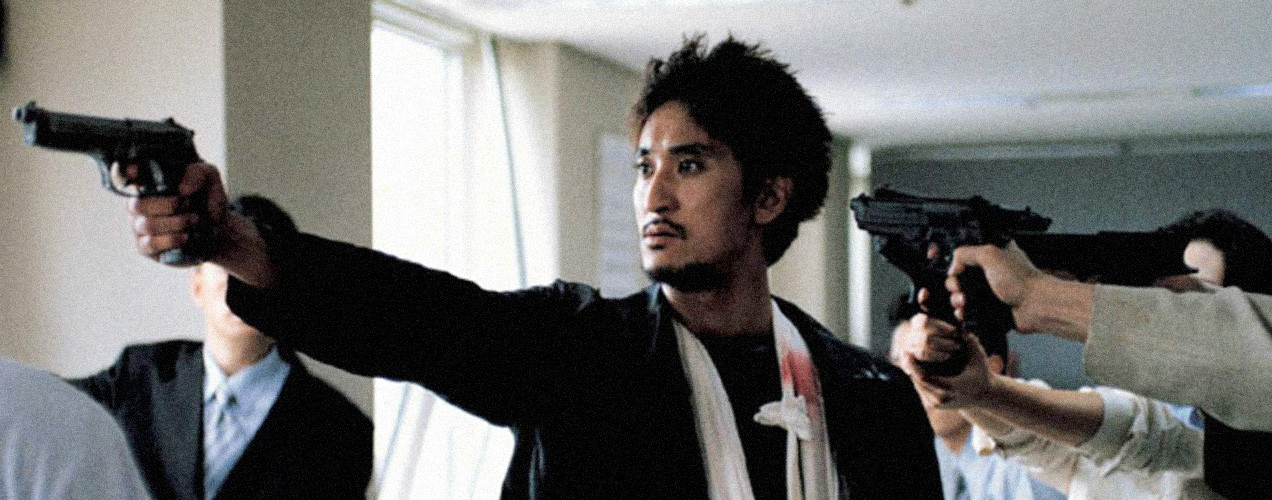

Guns & Talks

2001 / Jang Jin > A powerhouse cast (including The Man from Nowhere’s Won Bin and Sympathy for Mr. Vengeance’s Shin Ha-kyun) depict a quartet of assassins who are more of a dysfunctional family than a professional troupe. Jang’s direction results in a light-hearted, though poignant, black comedy: Amidst killings and a detective on their tail, they love and enjoy the little things in life. Guns & Talks was a relatively big hit in Korea, but unfortunately came out before Korean cinema really took off in the West. There are genuine laughs here that are in dire need of greater appreciation.

Punch

2011 / Lee Han > Punch is not a blockbuster. It’s about a poor high school kid growing up with a disabled father hellbent on dancing at a cabaret. It’s about mothers and being an outsider in a closed off world. It’s about fathers and sons and teachers and students. Most importantly, it’s about knowing that one cannot separate all these, that in the evermore complicated world we live in, everything converges at once, and we must learn to find solace in such traffic. And yet, maybe that’s why the film sold 5.3 million tickets in South Korea (or a tenth of the population). In every aspect of the film, there’s something to identify with. And while Punch isn’t glossy, Lee’s direction has shadows of Ozu’s Floating Weeds in its relatively gentle approach to otherwise serious matters.

Centered around a subdued effort by Yoo Ah-in, who himself was a drop out and rose through the ranks as an independent actor, Punch successfully converges the aforementioned topics into a calming, enjoyable piece of work that touches upon, most interestingly but within respectable context, the institution of international marriage. Wan-deuk, the film’s Korean namesake, discovers that his mother is Filipino. Combined with a hunchbacked father, the duo is a troubling mix for any teenager. Yet with the guidance of a teacher (who also happens to be his next door neighbour), he pushes through while learning some kickboxing along the way. At its weakest, it’s charming. At its strongest, Punch exposes a sizable majority of the Korean population to the optimistic end of broken homes. All this being said, it does one thing more…

Choi Min-sik (Oldboy), Song Kang-ho (Memories of Murder) and Sol Kyung-gu (Peppermint Candy): For the last decade plus, these three have been the male triumvirate of Korean cinema. Their range, skill and ability to carry films even with minimal screentime have been a gift to moviegoers, but now we must work on adding a fourth: Kim Yun-seok. Active throughout the 2000s, Kim truly broke out as the morally melted cop-slash-pimp in Na Hong-jin’s The Chaser in 2008. He followed that up with a grinding, fearless performance in Na’s follow-up, The Yellow Sea, where he’s a Korean gangster from across the waters. And now comes his turn as an enigmatic teacher whose moral compass seems a bit off. It’s a role that’s vastly different from the hard-edged nature of his previously noted efforts, but it’s one that he owns. Yoo and Kim’s back-and-forth rapport is a joy to watch and keeps the film from becoming an out-and-out melodrama.

To fully capture the impact of Punch in the Korean mindset, it should been noted that Filipino immigrant Jasmine Lee, who plays Wan-deuk’s mother, has been shortlisted by the majority-controlling Saenuri Party as a potential candidate. Whether this is smoke and fog doesn’t matter. The fact that this is even a possibility is significant in Korean culture and politics and speaks to the impact of the film.

Countdown

2011 / Huh Jong-ho > A family melodrama wrapped inside another melodrama about society’s inability to cope with mental disabilities sprinkled with some bloated action and uninteresting, stereotypical characters who are part-time criminals but generally okay-to-good people. Actually, one of them is a “bad” guy, though he’s kind enough to numb your legs before he breaks them. Novel, right? But let’s not kid ourselves: Countdown has basically no rhyme or reason to exist, and in the process, wastes a performance by the great Jeon Do-yeon (winner of Best Actress at Cannes in 2007 for Lee Chang-dong’s Secret Sunshine) and a stoic but relatively enjoyable Jeong Jae-yeong. This is, in many ways, the worst of Korean cinema: Mediocre, repetitive, unimaginative—the counterpart to Hollywood’s run-of-the-mill blockbusters.

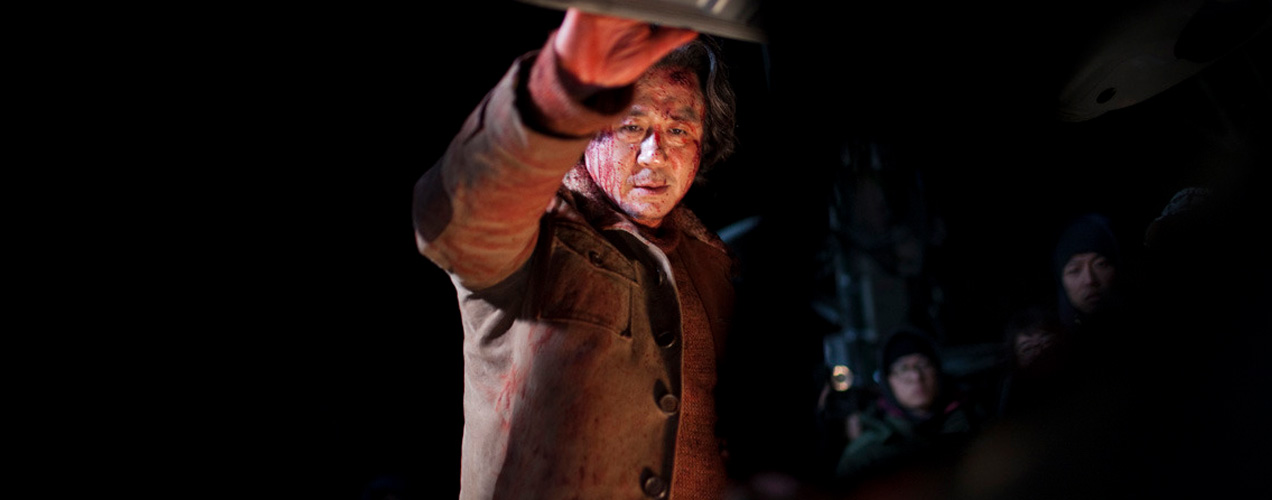

I Saw the Devil

2010 / Kim Ji-woon > Kim has defined himself as one of the most versatile mainstream directors in Korean cinema. With outings that include the very good neo-noir in A Bittersweet Life, a Western steampunk epic in The Good, the Bad and the Weird and his foray into the English language with Last Stand later this year, it’s little surprise he was able to secure two of Korea’s top actors for I Saw the Devil: Lee Byun-hun (who many in the U.S. know as Brian Lee a.k.a. Storm Shadow in G.I. Joe) and Min Sik-choi (who, known widely in the West for his role as Oldboy, makes a long-awaited return to the big screen).

There’s no smoke screen here: I Saw the Devil is about vengeance in the best way possible. Or is it the worst? That may, in fact, be the central question at bay. In his quest to avenge his wife’s death, a government agent falls so deep down the rabbit hole that we’re asked to second-guess how far we’d go to satisfy our deepest desires for revenge. But the lessons here aren’t anything extraordinary. We walk away feeling mildly disgusted with ourselves not because of the gruesome violence we’ve been exposed to, but because it didn’t mean much. Had this been made by a lesser filmmaker with lesser actors, it would have been naturally panned. But Kim, at the very least, knows how to direct an entertaining thriller that plays out with few visible regards for a moral compass. And though he’s slightly late to the game—the genre has become so saturated over the last decade that the film’s twists become relatively predictable—the film still works as a misdirection from our daily lives where we’re expected a greater level of human compassion.

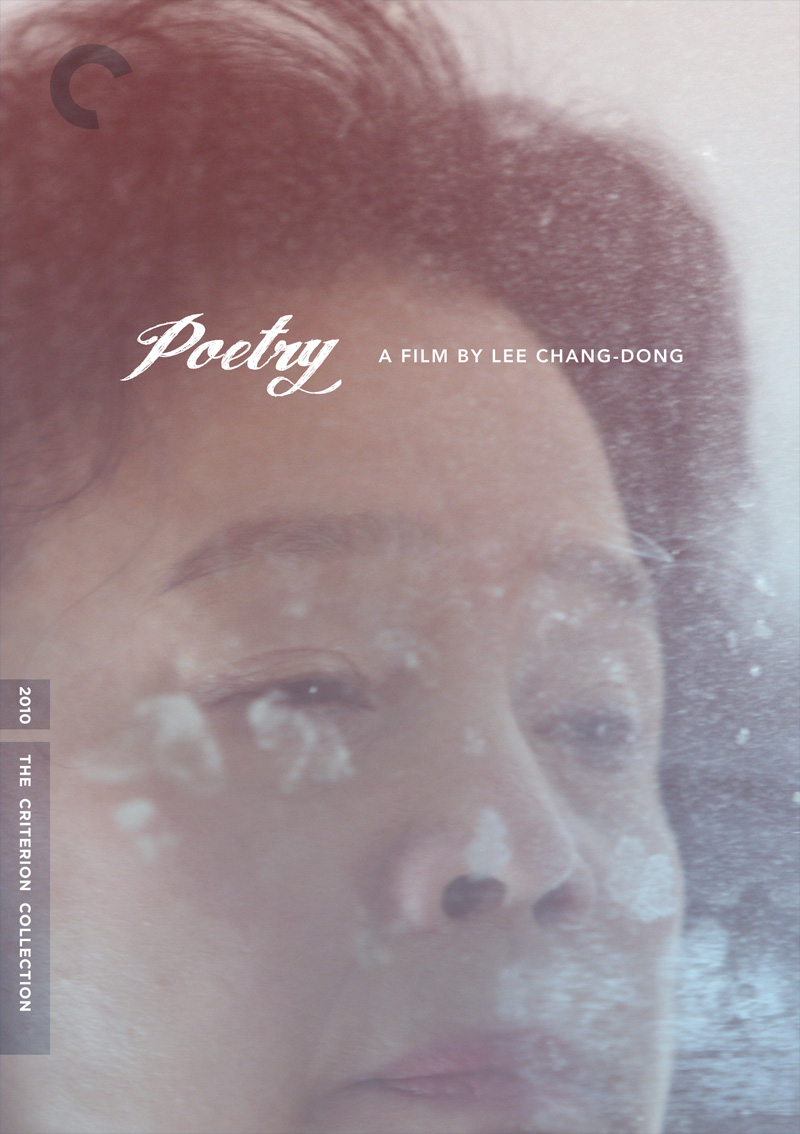

Poetry

#1: Poetry by Lee Chang-dong. In the ten days leading up to the 83rd Annual Academy Awards, I listed my ten favorite films of 2010, each accompanied by a custom Criterion Collection cover inspired by Sam Smith’s Top 10 of 2010 Poster Project.

2010 / Lee Chang-dong > After a minor “hiccup” that earned Jeon Do-yeon Best Actress at Cannes for Secret Sunshine, Lee is once again at the top of his game. In three feature films (Peppermint Candy, Oasis and now Poetry), he’s covered ground on the psyche of the Korean man, love in the darkest corners of humanity and the perils of aging in modern society. His ability to so seamlessly combine the brutal strength of the human condition with a probing yet tactful eye makes him arguably the greatest of all contemporary Korean directors.

Yoon Jeong-hee’s masterful performance (the best of the year, I’d argue) guides us in Poetry. She is Mija, an older woman who seems to be losing her mind. She takes care of her moody, borderline insolent grandson while her daughter is M.I.A. She works as a part-time maid to pay the bills and stay busy. One day, she decides to enroll in a poetry class at a local community center. From the onset, we get the basic situation: The last century has been very unkind to aging parents who get left behind as their children take advantage of relocation. (The ease of remittances eases a guilty mind, but it doesn’t make up for lost time.) Lee, however, doesn’t transfer upon us the blame for Mija’s current state. In fact, his habit for developing characters who learn to control their destiny is what makes him such a fine cinematic craftsman.

Over the course of the Poetry, Mija rekindles her relationship with the cruel world she’s lived in for so long. Many of us don’t realize the daily atrocities that occur until we find ourselves in the mud with others, and Mija is no different. Lee is not a flashy director: Every scene flows into the next without extra baggage. We know what’s happening, but we’re more interested in seeing things unfold than wanting an instant resolution. The process matters. The core conflict in the film, which is best learned while viewing (and may be spoiled immediately by most reviews), creates such a moral conundrum that there would be no consensus if viewers were polled on a course of action. Whether we agree with Mija or not, we still want her to find the strength to fight for what she believes is right. Poetry is not a melodrama. It is not about the underdog coming out victorious. As Mija writes her poem, there is a solemn tone of acceptance that the world will go on—but we know this acceptance has a price, and what’s important is that we fight with her so that only she, independently, gets to judge its true value.

The Man from Nowhere

2010 / Lee Jeong-beom > Though the title hints at classic film noir, The Man from Nowhere is a clear-cut actioner with brutal and often exciting fight sequences mixed with overflowing emotional padding. Aside from a seemingly complex plot that has no real consequence, there are simply too many long shots with sorrow-filled melodies to take the film seriously. In retrospect, I’m convinced that the 6.2+ million tickets sold in its domestic market have been due to star Won Bin’s abs. But his glowing stomach aside, the film effectively works as a melodramatic version of Taken. There’s no doubt that if you could trim some of that sentimentality, the outcome would be far superior.

2010 / Lee Jeong-beom > Though the title hints at classic film noir, The Man from Nowhere is a clear-cut actioner with brutal and often exciting fight sequences mixed with overflowing emotional padding. Aside from a seemingly complex plot that has no real consequence, there are simply too many long shots with sorrow-filled melodies to take the film seriously. In retrospect, I’m convinced that the 6.2+ million tickets sold in its domestic market have been due to star Won Bin’s abs. But his glowing stomach aside, the film effectively works as a melodramatic version of Taken. There’s no doubt that if you could trim some of that sentimentality, the outcome would be far superior.

Breathless

2009 / Yang Ik-joon > Raw, brutal and absolutely beautiful. When the star/director Yang came out and said, “Fuck the Korean film industry,” he meant it. Since 2005, Korean cinema has forgotten what made it so fantastic. It dared to do things global cinema was failing at. Whether it was the entirely unconventional roots of Shin Ha-kyun’s alien catcher in Save the Green Planet, the magical romance in My Sassy Girl or the twist of a lifetime in Oldboy, it’s been a long time since the country’s put forth anything worthy of conversation. Well, this is it: Not since Gary Oldman’s underappreciated Nil by Mouth have we seen domestic violence treated with this kind of uncompromising passion. And while passion may not seem like a word to describe a film of unabashed violence, it’s hard to argue that the violence of man is founded on a kind of ignorant, blind intensity that leads him to do things that don’t always make sense. Sometimes he doesn’t understand it himself until it’s too late. Breathless is that kind of film, where things happens as you would expect them to, no holds barred. Its anger is saddening but organic. There is no sentimentality, just the force of raw energy that devours all of us. The heart stirs immensely in this one, and if it doesn’t, I’d be hard pressed not to send you to the doctor to make sure you’re still ticking.

2009 / Yang Ik-joon > Raw, brutal and absolutely beautiful. When the star/director Yang came out and said, “Fuck the Korean film industry,” he meant it. Since 2005, Korean cinema has forgotten what made it so fantastic. It dared to do things global cinema was failing at. Whether it was the entirely unconventional roots of Shin Ha-kyun’s alien catcher in Save the Green Planet, the magical romance in My Sassy Girl or the twist of a lifetime in Oldboy, it’s been a long time since the country’s put forth anything worthy of conversation. Well, this is it: Not since Gary Oldman’s underappreciated Nil by Mouth have we seen domestic violence treated with this kind of uncompromising passion. And while passion may not seem like a word to describe a film of unabashed violence, it’s hard to argue that the violence of man is founded on a kind of ignorant, blind intensity that leads him to do things that don’t always make sense. Sometimes he doesn’t understand it himself until it’s too late. Breathless is that kind of film, where things happens as you would expect them to, no holds barred. Its anger is saddening but organic. There is no sentimentality, just the force of raw energy that devours all of us. The heart stirs immensely in this one, and if it doesn’t, I’d be hard pressed not to send you to the doctor to make sure you’re still ticking.

Dream

2008 / Kim Ki-duk > Again, Kim further solidifies his rank as the most polarizing director in Korean cinema. He’s usually hit or miss, and sadly, even with the presence of Odagiri Jo, Dream comes off as a wasted opportunity. Sure, the movie is intended to be a bit of a puzzle, and nothing should have been taken at face value, but that alone doesn’t make it better. In fact, the film’s progression simply frustrates with its so-called cleverness. In some ways, this is a deconstructed version of Mulholland Drive, which is a film that you can’t help but respect even if you don’t like it. But in its deconstruction, Kim has dumbed things down to the point where there’s no meat on the bone, that the audience continually gnaws upon empty illusions. The only thing of real note happens to be Lee Na-yeong’s dramatic turn that can’t help but surprise in response to her previous outings (e.g. Please Teach Me English).

2008 / Kim Ki-duk > Again, Kim further solidifies his rank as the most polarizing director in Korean cinema. He’s usually hit or miss, and sadly, even with the presence of Odagiri Jo, Dream comes off as a wasted opportunity. Sure, the movie is intended to be a bit of a puzzle, and nothing should have been taken at face value, but that alone doesn’t make it better. In fact, the film’s progression simply frustrates with its so-called cleverness. In some ways, this is a deconstructed version of Mulholland Drive, which is a film that you can’t help but respect even if you don’t like it. But in its deconstruction, Kim has dumbed things down to the point where there’s no meat on the bone, that the audience continually gnaws upon empty illusions. The only thing of real note happens to be Lee Na-yeong’s dramatic turn that can’t help but surprise in response to her previous outings (e.g. Please Teach Me English).

Night and Day

2008 / Hong Sang-soo > For Hong, this is beyond return to form: It’s an impressive work that shoves aside much of the quirkiness of his previous stories and focuses on the loneliness faced by a Korean in Paris. Once again, we deal with themes of love, longing and faithfulness, but the plot devices are much more identifiable this time around. Instead of abstract meetings on trains, we have introductions and rekindling of past relationships. But beyond that, it’s hard to describe. It’s so layered that it’s nearly impossible to reach an emotional consensus upon the first viewing. But what it does do is stay with you afterwards, nagging, making you wonder if the decisions made in the film are akin to decisions you would make yourself. That’s definitely Hong’s hook, though—reveling in our self-doubts about life and the opposite sex. We watch his films to learn more about ourselves, and this is no exception.