2015 / Kabir Khan > As the second-highest grossing film in Indian history, you have to give this Salman Khan-vehicle credit for sending a strong social message to viewers: It doesn’t matter what religion, nationality or caste you are, just treat people like people and everything will fall into place. It’s unfortunate that many of the factors that probably led to its box office success—the unnecessary slow-motion shots, the heroic action sequences bordering on the fantastic, the suspension of disbelief needed for the central plot device to exist—also kept Bajrangi Bhaijaan from being exceedingly satisfying. But that may be a small price to pay for a story of Indian-Pakistani cooperation that may inspire a new generation to rethink its approach towards blind hatred.

Category Archives: South Asia

Paan Singh Tomar

2012 / Tigmanshu Dhulia > Bollywood continues to baffle: How can such amateur filmmaking be a critical darling? The fundamental problems of Paan Singh Tomar, a loose biopic of an army-athlete-turned-bandit, exist regardless of nationality or historical context. The barrage of constant, heavy musical cues, awkward cuts with rough pacing and obsessive use of shots that have no relevance all take away from the central story. On top of these, a solid performance by a miscast Irffan Khan is negated by shoddy character development that lacks consistent direction. (Do we ever really care about him?) And all of this is made worse by downright terrible performances by minor actors. Neither budgetary constraints nor lack of technical expertise are excuses for such a subpar production.

India has done well not to select Paan Singh Tomar as their entry into the Oscars for 2013. (Barfi! deserves it considerably more, and the quality difference between the two films are day and night.) The problem, however, persists: Bollywood moviegoers are too easily amazed by “new” cinema their country produces, even if similar cinema has been done before better elsewhere. And while being derivative isn’t necessarily a negative as long as proper due is given and quality is controlled, praising mediocrity devalues the perception of the whole industry.

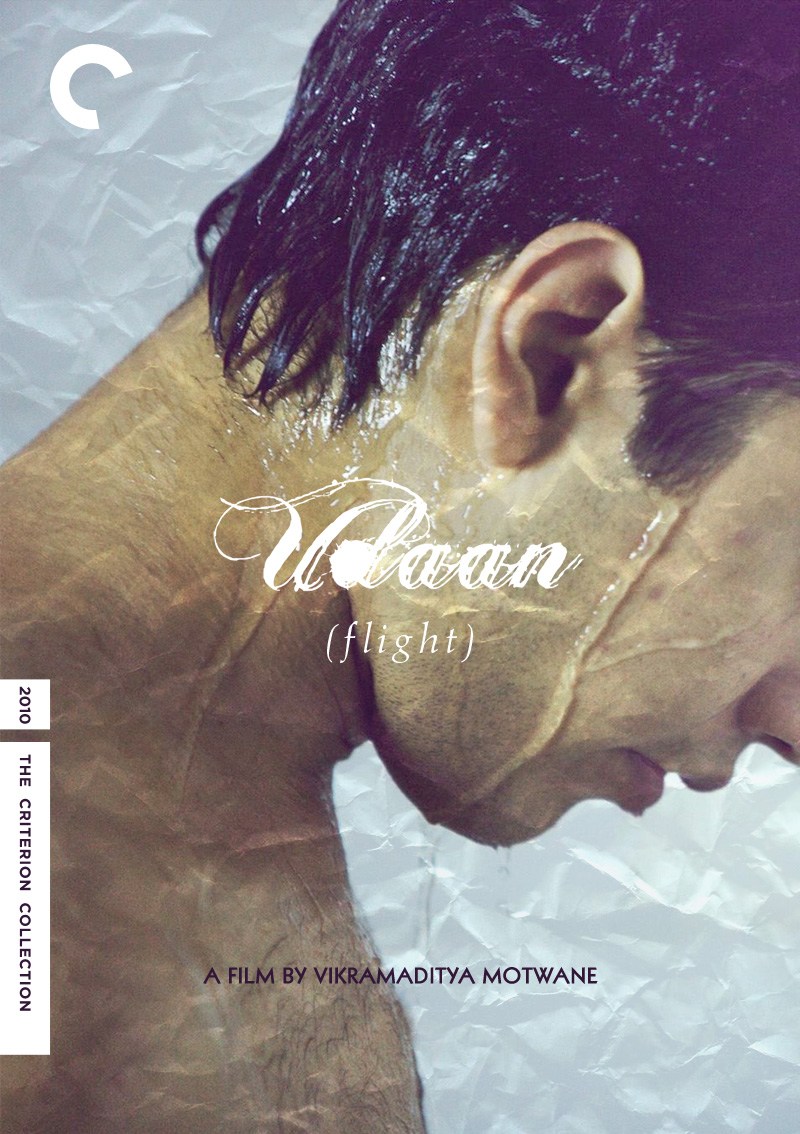

Udaan

#9: Udaan byVikramaditya Motwane. In the ten days leading up to the 83rd Annual Academy Awards, I listed my ten favorite films of 2010, each accompanied by a custom Criterion Collection cover inspired by Sam Smith’s Top 10 of 2010 Poster Project.

2010 / Vikramaditya Motwane > If the astounding box office success of the glossy yet heartwarming 3 Idiots can be attributed to the Indian populace wanting to believe in a life outside strict academia and careers in medicine or engineering, Udaan takes it a step further by integrating reality into the mix. The former succeeded by broaching the subject in a comedic manner, but had a sizable mistake in having a central character of extraordinary talents that limited identification. But in Udaan, Rohan, a good-natured 16 year old boy recently expelled from school, is an everyman. And we soon find that his dreams of being a writer are to be quelled after reuniting with his estranged father.

Flight, as the title translates, is about Rohan breaking free from what society had made him believe was important and necessary. It’s hard not to call his actions landmark in Indian cinema, especially for a film coming out of the Bollywood system (with both Motwane and writer Anurag Kashyap being successful with 2009’s Dev.D). For an industry that still finds full-on kissing controversial, the themes expressed here should theoretically create absolute outrage. Unlike the birds and the bees, family relations are too entrenched and rarely discussed about in such a candid manner. What the Western societies have debated in mainstream cinema for ages is once again being pushed out into the wild in India, signaling many of the great local directors of the past (think Ritwik Ghatak or Satyajit Ray) whose works have been lost on the masses. The ideas in Udaan aren’t particularly original, but how it approaches relations between fathers, sons and brothers is one worthy of discussion. Appreciation of the ending will depend on one’s moral compass, yet there’s something undoubtedly brave about it—for both the filmmakers to attempt such as well as the characters within.

3 Idiots

2009 / Rajkumar Hirani > There’s an easy explanation as to why 3 Idiots is easily the highest grossing film in Bollywood history, almost doubling the box office receipts of its nearest competitor: The film defines generations of Indians (and South Asians in general) and is relevant now more than ever. On the surface, it’s just a fun film with quite a lot of predictability, cheesy moments and phoned-in laughs. But the thematics of a generation lost to examinations and monetary success are rooted deep within the culture’s bones. Most Indian students, male or female, know the pressure of success in one of the world’s toughest educational marketplaces, the fight for a spot in elite private schools, combating parental pressure and the selflessness this all carries.

Dreams are often tertiary to jobs and family, but in 3 Idiots, Hirani has offered a glimpse of hope to the Indian youth. Chances are it will have little effect on how families work, how parents push their children to the edge, but the exploration, in all its glossiness, is a worthy cause that’s obviously been taken to heart by the country’s moviegoers. As long as it’s not taken out of context and mistreated as an Indian equivalent of Dead Poets Society, there is much satisfaction to be had. And who knew Aamir Khan (whose Memento-derived Ghajini holds that second all-time spot) could so convincingly play a college student at age 44?

Slumdog Millionaire

2008 / Danny Boyle > Boyle’s really hit me from left field on this one: Boasting one of the most impressive and varied filmographies in cinema today, I imagined this to simply be a heart-warming tale of rags-to-riches and romance. Well, that it is, and so much more. Slumdog Millionaire is conscious of the modern-day India, crisscrossing from the slums to India’s upper class while still approaching the shady underground gangsters and their counterparts (and every American’s favorite) the call center operator. Stylistically, it borrows as much from Boyle’s own Trainspotting as it does from City of God. The vibrant colors and sharp editing energize the film’s pacing so that the viewer’s journey is a non-stop feast of entertainment. And a soundtrack cutting M.I.A.’s beats and vocals only support that foundation. There are a couple of things to be understood, though: The story is fairly conventional, the “plot twist” happens in the beginning, so the viewer isn’t being suckered on, and it’s a bit predictable. But none of that keeps it from being arguably the most incredible, enjoyable film of the year. The whole experience is a crescendo that culminates with the kind of gritty satisfaction that no straight-edged family film can offer.

The Namesake

2007 / Mira Nair > It’s a rare thing that celluloid beats its paper foundation, but The Namesake does just that. Personally, I’ve found Jhumpa Lahiri’s writing style to be better fitting for short stories, but maybe I’m biased: The first two-thirds of the novel deal with things I’ve personally experienced, while the third is fairly uncharted territory. For that, maybe Nair’s pacing fit me better.

The film itself is graceful, respectful, ignoring the stereotypes that often plague cinema that crosses cultural boundaries (and for this, both Lahiri and Nair ought to be credited). It’s not perfect, but it has enough universal identification that it should be able to appeal to most of who have a chance to view it. The only dubious factor with the film is Kal Penn being casted for the lead role: He does a suitable job, but it’s just hard to forget that this is Kumar we’re talking about. The rest is quite appropriate, with special note to Tabu’s performance as the beautiful, maturing mother who can make or break the viewer’s heart.