2010 / Tom Hooper > Founded on a screenplay by David Seidler filled with clever quips, The King’s Speech is an enjoyable if sometimes too conventional re-creation of British history. It does play on the softer side of things (leaving out much of Edward VIII’s pro-Nazi sentiments) while too often accentuating the melodrama. But what really makes the film stand out are its two central actors: Colin Firth (who will probably win the Oscar even if his isn’t the singular best performance of the year) and Geoffrey Rush play off each other so delightfully that all fundamental shortcomings of the film are easy to ignore.

Category Archives: Southeast Asia

Boy

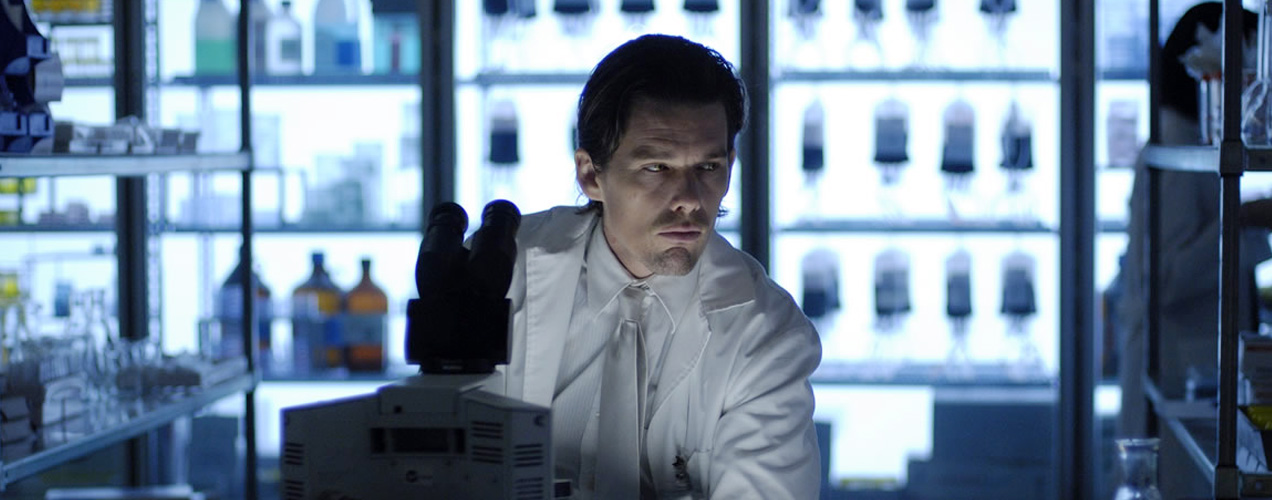

Daybreakers

2010 / Michael Spierig & Peter Spierig > Daybreakers starts out strong with a focus on creating atmosphere, context and a scientific approach to how vampires come to rule Earth, and then quickly teeters into a banal action clone that misses out on a chance to be a science fiction classic because of its shortsightedness.

Mary and Max

2009 / Adam Elliot > Elliot got on the radar screen with an Oscar for his oddball, tragic figure of Harvie Krumpet in 2003. Mary and Max, his feature debut, stars a core cast of Toni Collette and Philip Seymour Hoffman, the latter especially nailing his part as a middle-aged man with undiagnosed Asperger’s living in New York in the mid-70s. The former, a pre-teen girl lacking friends and beauty, becomes his penpal from the suburbs of Melbourne. And that’s where normalized expectations take a nosedive. The story has a lot of minor twists and turns, mostly idiosyncratic, running the thin line between quirkdom and absurdity. Had it remained a simpler story that ended in the finality of eventual happiness, it would have wasted its build-up with a sort of banal comedown. But Elliot hits a couple of heartstrings in interpreting his opinion of those who “suffer” from Asperger’s (and subsequently, a lot of other similar perceived ills): Never assume they are worse off than you, and never assume they need your help. Elliot drives this simple message home without insulting the viewer, and for that alone, the man (as well as his film) should be commended.

Serbis

2008 / Brillante Mendoza > Premiering at Cannes in 2008, Serbis drew a lot of controversy for its explicit sex sequences and—wait for it—boil popping visuals (you’ll have to see it to know what I mean). And in 2009, Mendoza scored a coup for the Philippines by taking home the best director prize from the same festival for his follow-up Kinatay. The world can thank him for two simple aspects of his style seen in this movie: He shows a part of his country that most don’t know about, as a family in Angeles struggles to survive by running a theatre running heterosexual pornography for a homosexual clientele. And more interestingly, he approaches this culture with a kind of hands-off, natural viewpoint that feels neither forced nor sensational. There are scenes in the film that initially contain shock value, but over a complete run-through, the whole thing works surprisingly well. As my introduction to Filipino cinema, I feel fairly confident that we’ve only scratched the surface. But if this is any indication of what’s to come, the industry should have a brighter future. Its colonial history and the Marcos “reign” along with its positioning in the current globalization climate gives it access to stories that maybe only Thailand can rival.

Eagle vs Shark

2007 / Taika Waititi > Quirky can work, but it has to work with the film and its characters, not against them. In Eagle vs Shark, the joke is mostly on the male lead (Jemaine Clement from Flight of the Conchords) and much of the cast surrounding him. It’s supposed to be a romantic comedy, but the film progresses more as a portrayal of family dysfunctionality. That would have been fine if it weren’t for the fact that only the female lead (who, played by Loren Horsley, is a quiet joy to watch) shows any emotional development. In the end, what seems to annoy/anger me the most is the sheer human patheticness that’s accepted. Films like Oasis approach those who aren’t capable of intertwining with society on their own behalf with intelligence and tact, but here, it’s just utilizing them as fodder for cheap, nervous laughs.

Be with Me

2005 / Eric Khoo > Be with Me is structurally flawed. On a pure fundamental basis, the trio of stories that create the network within the film should each have a similar level of importance and screentime to keep the balance, right? Khoo decides otherwise and starts to increase the focus on a specific one as the film progresses, weaving in a documentary style because, as we find out, one of the characters is actually a real person—Theresa Chan, the Singapore equivalent of “Helen Keller.” This mismatch of fact and fiction is jarring to us because we don’t know whether to take this as entertainment or a life lesson.

The film’s style, with a total of 2.5 minutes of dialogue in its ninety-three minute span, is sparse but elegant. Each shot is gorgeous in its own right, and the transitions are apt and don’t reek of style over substance. The unfolding of each story is judiciously spliced and paced to keep enticing us. The real meat, once it gets rolling into its third and final act, is its open-ended theory on love and loneliness. It’s a thesis of sorts in understanding the have and have-nots, and its true beauty is in the manner in which it translates this fiction into a real-life perspective. It’s heartwarming but strong, quaint and unforgettable.

4:30

2006 / Royston Tan > Similar to short film director Tan’s first feature film 15, I found myself hoping that 4:30 was at least half the timespan of its final cut. The meat here is spread quite thin, with a few poignant moments that may linger long after. The story of a boy’s loneliness in the absence of a father (or in the presence of a stranger) is a worthy one, and this is one hell of a try at it. Unfortunately, attention spans are tested, and it almost seems like Tan wants us to do a considerable amount of the legwork to make it happen. And while I’m not always against doing that legwork, it would be nicer if its length was fitting.

Invisible Waves

2006 / Pen-Ek Ratanaruang > It’s hard to gauge if those who liked Last Life in the Universe will also like Invisible Waves. But those who have the patience for Pen-Ek’s multinational opus—with Japanese, Korean, Chinese and Thai stars represented and much of the dialogue in English—will be rewarded by the film’s ability to slowly but surely question the value of loyalty, self-worth and happiness.

Not surprisingly, the film is also absolutely gorgeous thanks to the hands and eyes of cinematographer Christopher Doyle. Its pacing is a little skewed, with each third of the film speeding up at twice the pace of the previous. And while this causes the film to start slowly, it successfully mimics the protagonist’s mindset so that we feel the similar type of rush in the latter third as he does. The dialogue in Invisible Waves is seemingly simple, but always struck certain chords, however small. Similar to its predecessor, it’s somewhat hard to explain exactly why I enjoyed it so much. But I did, and for that I can do little but to recommend it wholeheartedly to anyone who’s willing and able.

Citizen Dog

2004 / Wisit Sasanatieng > Take Amelie, increase the color saturation, replace Paris with Bangkok and add some crack. That about sums up Citizen Dog: a quirky, oddball romantic comedy that has its own fair share of imagination to keep itself from simply being dubbed a copycat.

Its most unfortunate act may be that it starts off so strong (in terms of original content, witty storyline and sheer pacing) that halfway through it fails to keep up. Once that steam runs out, the style no longer works or fits, and the viewer is left stalled, even bored. Moreover, the peculiar subplots work fine when in small doses, but the whole “plastic” storyline was dead at arrival. However, this remains a wonderful watch if only because one gets to witness the further maturation of Thai cinema as well as some very memorable characters in their habitat.