1985 / Martin Scorsese > Dated and often purposefully silly, After Hours is effectively Scorsese’s love letter to 1980s New York, or as the film’s working title would aptly have declared it, A Night in SoHo. For those, like myself, who missed the grungy glamour that made the area south of Houston Street such a haven to artists, this is a way to travel back in time. It’s incredible to compare the grimy, scuzzy streets of yesteryear to the buzzing, higher-end commercial district it is now. But aside from that, it’s a bit ho-hum. Centered around a typical office worker’s overnight misadventures, the film has its fair share of characters, of which all but one work on the periphery. This is not the type of extraordinary journey we expect out of Scorsese, but rather a small detour where he’s able to create a work of art that’s filled with some small joys even if they’re short of a full circle in the end.

Category Archives: United States/Canada

Lolita

1962 / Stanley Kubrick > Say what you want about the Hays Code, but Lolita is a clear example of where it worked wonders: Kubrick was forced to adapt Nabokov’s classic for the screen with a level of creative subtlety that allowed its sexual proclivity to be hidden in plain sight. As the word “Lolita” itself has become part of our everyday vocabulary, it’s now nearly impossible to go into the film with any expectation of shock. Thus the film not doling around on the erotic and, instead, focusing on the madman-at-hand actually benefits the storytelling. Admittedly, it lacks the in-depth analysis of Humbert Humbert, played so tautly by James Mason, but what it leaves to our imagination is much more preferable. We’re allowed to fill in the gaps of what kind of background forces upon an older man the preference of younger, so-called “nymphettes” instead of women of similar age.

Unlike the novel, which is written from the viewpoint of a highly unreliable, subjective narrator, the film takes a couple of steps back but still keeps us within arms’ reach of the situation. Across from Mason, 16-year-old Sue Lyon’s performance as the titular character is astounding in its sophistication. It’s hard not to wonder if she’s an older actress playing the part of the 14-year-old, but such is the effectiveness of her “range” that has the feel of anywhere from 13 to 25. All the while, there’s something very contained in her sensibilities that makes us wonder how much of what we perceive in the film is morally apt. Nabokov was considerably more black and white about Humbert’s nature of obsession, but Kubrick’s not nearly as judgmental. And the film is better for it—even with Dr. Strangelove’s forceful and unnecessary cameo.

Margin Call

2011 / J.C. Chandor > Actual Bloomberg terminals and financial terminology without explanations: Have we come this far in cinema? Can we actually approach Wall Street without caricaturing it? Chandor’s one-night-before-the-crisis take of a fictional Bear Stearns-wannabe is a giant step in filmmaking. Finally, we have a thoughtful, deliberate film about the crisis without condescension or a moral high-ground. Amidst the cries of crowds at Occupy Wherever, we are charmed with a thriller that allows us to track the moment of discovery to the impending fallout, all while focusing on the humanity of the situation. It doesn’t matter whether one is a socialist or a capitalist, the reality is that truth often gets pounded by hearsay as long as it serves a greater purpose. But every story has two sides, and Margin Call does its damnedest to tell both. Were it not for the gravely miscast Demi Moore and slightly heavy expository dialogue, this could really have been one for the books. Still, the film is a must-see for anyone trying to dig into the psyche of those who stood at the foundation of a crisis that some will never forgive.

Drive

2011 / Nicolas Winding Refn > The worst thing about Drive is the hideous, misuse of Mistral during the credits. You sit there, as Ryan Gosling drives into the night, wondering if you’ve been transported to a grittier version of Miami Vice. Maybe genre films remain an insular interest because the kitsch factor is too embedded in their culture? After all, this is the font that graced the intro of television’s Night Court.

But then the film unfolds. And sets up. And takes off. And during this ride, which can effectively be described as a classic noir tale with a penchant for real violence, there is nary a hole that can be poked. Every second is necessary, every shot elegant, every piece of music supports the action on the screen. Every question normally asked of a film, this one answers either with some level of extrapolation or faith in its characters. Gosling, credited simply as “Driver,” is reminiscent of Clint Eastwood’s The Man with No Name. We gradually discover over time that he’s exactly the kind of person missing in 99% of Hollywood cinema: One that doesn’t cop out. That, in itself, is a tremendous victory.

As those who’ve watched his Pusher trilogy as well Tom Hardy’s brilliant, psychotic coming-out party in Bronson can testify, Winding Refn is a momentous talent. In fact, the lyrics of Kavinsky and Lovefoxxx’s “Nightcall,” which overtures the opening sequence, speaks of both the director as well as Gosling’s Driver: There’s something about you, it’s hard to explain. They’re talking about you, boy, like you’re still the same. In short: They are not to be underestimated. Drive shows the maturation of Winding Refn as a controlled director, Gosling as an action star and together they’ve come up with a fine piece of entertainment that’s a beauty to look at, satisfying to watch and evocative enough to remember.

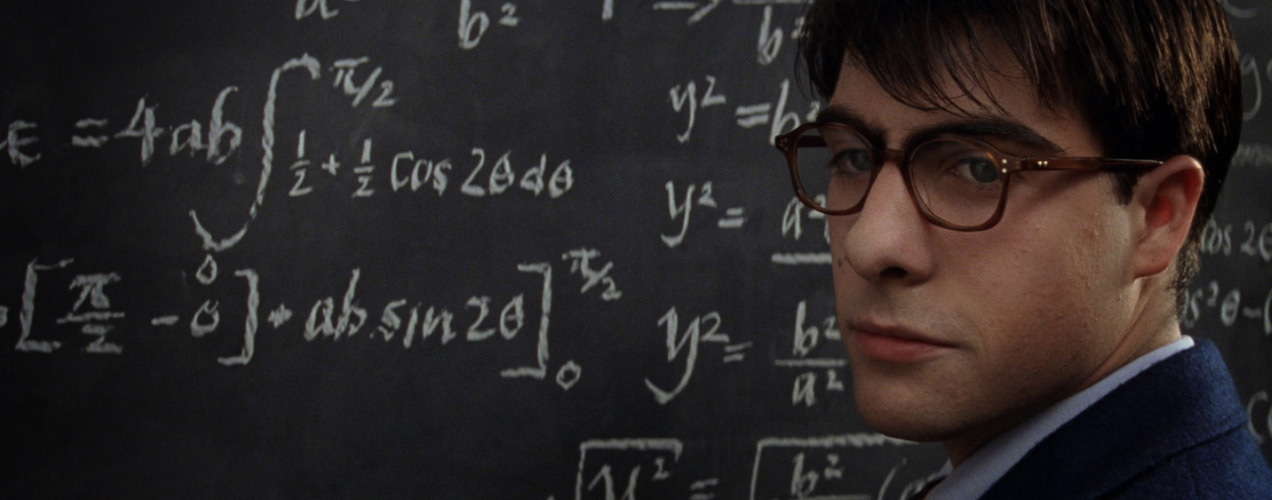

Rushmore

Rushmore by Wes Anderson is the yearly favorite from 1998 as listed in Life as Fiction (Through Time): An Exercise in the Clockwork and Constriction of Cinematic History, a project to chronicle my favorite film from each year since 1921.

1998 / Wes Anderson > Not sure how much my familiarity with the soundtrack had to do with it, but my latest viewing of Rushmore was a completely different experience than I’d previously recalled. Seeing it in theatres upon release, when Anderson’s tactics were still fresh, the first half was all the rage while the second half seemed banal at best. But over time, that first half became a sort of gimmick, something to create an illusion of substance when in reality it embodies much of the indie quirkiness that continues to plague current cinema. But now, multiple Anderson films later, I’ve finally realized what makes the film tick isn’t its first half, but rather the second half, which maintains a sense of quiet rumination filled with the appreciation of living and acceptance.

In ways, this is as unusual a coming of age film as there ever may be. While Jason Schwartzman’s Max Fischer isn’t immediately someone to identify with, his emotional see-saw with Miss Cross (played by the elegant and lovely Olivia Williams) provides an intangible yet definite hook for us to latch onto. He seems the antithesis of what we see in Dangerous Minds, yet in many ways, he’s exactly similar. Nobody said you had to deal with guns and drugs to be a delinquent—You can also do it with “extracurricular activities” like building aquariums on the baseball diamond or tending bees instead of taking exams.

Also impressively, no Anderson film has used music as effectively as Rushmore: The Who backing the revenge sequence, John Lennon supporting Bill Murray’s hopeful Herman Blume and Max’s road back to grace and Miss Cross taking Max’s glasses off to Ooh La La by Faces (where the minor quiver on Williams’ lip is one of the finest moments in my personal cinematic history). All of these are further impacted by the calculated camera work of Richard Yeoman. So beautiful, in fact, that the curtain scene at the end has forever become etched in my memory.

Originally posted on October 25, 2008 before inclusion into (Through Time).

Sucker Punch

2011 / Zack Snyder > Never in my life have I so strongly felt the need for a film to be a video game—and just that. Snyder’s first attempt at original material shows his lack of storytelling prowess, as Sucker Punch somehow turns glorious visuals and sexy schoolgirls with cleavage into something that’s only a notch better than a mindnumbing bore.

Maybe I’m extra underwhelmed because the initial teaser was one of the best I’d ever seen. Expertly composed, it promised a fantastic adventure into the mind of a young girl in her fight for survival. A combination of dragons, samurai and zombie Nazis on a foundation of steampunk whetted our appetites for an exciting genre-bender. But Sucker Punch ends up failing for the same reason Snyder should be given some credit: He made it into a personal film instead of one that audiences would enjoy. One could argue that his intention was to combine his trademark visuals with the philosophic backbone of Bergman, but he simply didn’t have the vision and/or chops to execute that effectively. Instead, it’s predictable until it becomes silly. Emily Browning, who was excellent in Lemony Snicket’s A Series of Unfortunate Events, is very much out of her depth here. Jamie Chung is wooden. Vanessa Hudgens has no lines worth repeating. Scott Glenn is a joke (though possibly on purpose). Abbie Cornish and Jena Malone are too good for the script. And as one of the most well-known contemporary, mainstream auteurs, Snyder has to take the blame for this mess. Still, if there’s something of value here, it’s that he was able to get a big budget film onto screens with his vision mostly intact, even if it depended on some of our basest fetishes for its appeal.

Out of the Past

Out of the Past by Jacques Tourneur is the yearly favorite from 1947 as listed in Life as Fiction (Through Time): An Exercise in the Clockwork and Constriction of Cinematic History, a project to chronicle my favorite film for each year from 1921 to the present.

1947 / Jacques Tourneur > It’s pretty obvious why David Cronenberg paid homage to Out of the Past in A History of Violence: If you’re going to put a twist on a genre, why not pay respect to its standard-bearers? Tourneur’s take on classic film-noir is thoughtful and riveting. The directing is meticulous, setting up a moody atmosphere, taking time to play out scenes that would otherwise have been rushed and making sure each of our characters are aptly developed. I can also now finally understand why Robert Mitchum was such a big deal. His quiet poise calls upon him an honest appearance while underneath he has the ability to carry deeper, darker secrets. And in a film where Jane Greer counters him as a dame of great beauty and equally great villainy, both work together balancing each others’ brilliant performances.

But fundamentals aside, Out of the Past is more notable for its congruence of issues: Lies, murder, secret pasts, infidelity, love, hope, greed, happiness. Novelist and screenwriter Daniel Mainwaring threw the kitchen sink plus some toiletry in the story’s mix of ingredients. But what amazes is how well it all works out. The final scene with the boy stands the test of time as one of those moments that leave you wondering the improbable quality of the film you’ve just witnessed. These days, the descendants of noir have simply too much cynicism or lack of storytelling skills to be this effective.

Originally posted on February 11, 2009 before inclusion into (Through Time).

Somewhere

#2: Somewhere by Sofia Coppola. In the ten days leading up to the 83rd Annual Academy Awards, I listed my ten favorite films of 2010, each accompanied by a custom Criterion Collection cover inspired by Sam Smith’s Top 10 of 2010 Poster Project.

2010 / Sofia Coppola > For the third straight film, Coppola dives into the emotional troubles of the rich and famous. While the general perception may be that money has the ability to buy one happiness, the truth is that wealth is a relative meter of comfort and works only as a superficial divider amongst the populace. One of the great examinations of this came from Nick Smith in Metropolitan: “It’s a tiny bit arrogant of people to go around worrying about those less fortunate.” The theory works completely in reverse as well. Mistakes can be made by anyone, regardless of job, money or location. It’s how we deal with those mistakes and what we learn from them that actually defines us.

In Somewhere, we follow Johnny Marco (played without pretension by Stephen Dorff), a Hollywood star lacking energy for life. We take in his aimless minutiae until his daughter Cleo pays him a visit. In Cleo, Elle Fanning is able to bring forth the grace of life that wakes up sleeping giants. In what may be my favorite supporting female performance of the year, her simple smiles keep our attention, and we understand, almost instantly, the value of truly loving someone away from all the glitz and glamour the world so continuously taunts us with. Sure, she’s still able to order expensive room service in an Italian hotel because of her father’s fame, but it’s more important to think of the loving kinship here than let our mechanical jealousies take precedence.

Of all films from 2010, Somewhere might be the one that I find with the most rewatchable. Every scene mesmerizes in its naturalness—including a wondrous episode of Guitar Hero that many of us can identify with. In contrast to Nicole Holofcener’s Please Give, Coppola doesn’t really force any resolutions. Johnny’s emotional curve remains relatively flat throughout because, let’s face it, some of us never learn our lessons. And while that’s a tragic truth to admit, it’s a link that sticks.

The Social Network

#5: The Social Network by David Fincher. In the ten days leading up to the 83rd Annual Academy Awards, I listed my ten favorite films of 2010, each accompanied by a custom Criterion Collection cover inspired by Sam Smith’s Top 10 of 2010 Poster Project.

2010 / David Fincher > Everything’s been said about Fincher’s take on Mark Zuckerberg and the birth of Facebook. Ambition, betrayal, Aaron Sorkin’s biting dialogue—all these add to 8 Oscar nominations and near-universal acclaim. But sadly, The Social Network may be one of those films that feel so “important” that it’s hard for any self-conscious viewer to admit in disliking it. It’s technically sound filmmaking that lacks the heart which might propel The King’s Speech to Best Picture. It’s a film for those who thrive on competition and know, because of that drive, how easy it is to lose family and friends. It describes a culture all too common in upper academia of the northeast and Silicon Valley, where intelligence and wealth intersect in devastating fashion.

Jesse Eisenberg’s Zuckerberg is cold, defensive. But what makes his Best Actor nomination worthy is the the vulnerability he shows throughout. It’s amazing, in fact, how much one’s insecurities actually work as a motivator. Whether the story’s true or accurate doesn’t actually matter, though. This is a movie; it’s effectively fiction. And for that, Eisenberg, Andrew Garfield and Armie Hammer brilliantly bring to life the game’s players with unique characteristics, often built on Sorkin’s snarky writing. The much-lauded screenplay isn’t perfect by any means. People don’t talk in such witty quips, but thankfully Sorkin left out much of his liberal slant—there’s a different kind of politics at play here.

Unusually, The Social Network works as a motivator as much as Rudy or Breaking Away. You watch these guys battle it out and wonder if you could have done the same. Maybe not everyone goes to an Ivy league school, but everyone has ideas. And it doesn’t matter if you’re in a small town in the corner of Idaho or at Harvard Square, these ideas can be put to work. The Internet has made anyone’s ambition possible. And suddenly, in some way, in Zuckerberg, there’s a bullseye to target.

Blue Valentine

#6: Blue Valentine by Derek Cianfrance. In the ten days leading up to the 83rd Annual Academy Awards, I listed my ten favorite films of 2010, each accompanied by a custom Criterion Collection cover inspired by Sam Smith’s Top 10 of 2010 Poster Project.

2010 / Derek Cianfrance > A brutally honest dissection of a crumbling marriage. Young love, in and out of love. The process is painful, but what sets Blue Valentine apart from a pityfest is Cianfrance’s ability to conjure the magical moments that made all the pain worth it. The cynic in me argues that romance is an ideal brought forth by the media for capitalist gain. But that’s just silly: We all want to be loved, but it just so happens that we don’t always know the best way to be loved. It’s become a game of politics in the modern-age, driven at its core by the free flow of information and ease of physical travel: Twenty years ago, it was much harder to cheat on your husband. Now you can flirt all day as SxyGrl23 on a multitude of adult dating sites. And if someone catches your eye, Southwest Airlines will help you get away.

Boredom punishes us and jealousy weakens our dedication. That’s why relationships are hard work. That’s why we should cheer for those who don’t give up.

The film is founded on the incredible performances of Michelle Williams and Ryan Gosling. The latter, by my count, is the best I’ve seen from 2010—though the Academy was quick to ignore him completely. They carry every scene with such raw beauty that it’s hard not to believe in every simple act. Nobody’s a villain. Everyone has their reasons, no matter how opaque. The brilliance of the script is its inability to judge people for being human. In fact, not since 2006’s Flannel Pajamas have we experienced such objective adoration for the act of romance and its subsequent disenchantment. Alas, if there’s another reason to cheer, it’s that Blue Valentine and Winter’s Bone have given us proof that independent cinema without pretension is alive and well in America.