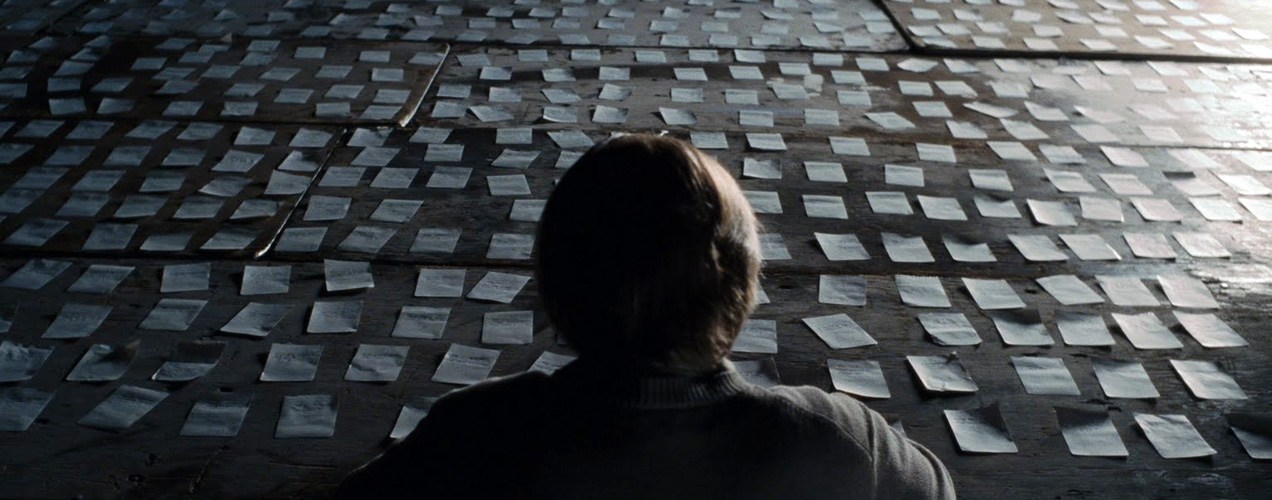

2009 / Marc Webb > This started out well. I can understand the premise of a so-called serious story about how relationships are in the real world. Hollywood doesn’t produce real world stories because they don’t sell tickets. Though frankly, they don’t sell tickets because Hollywood isn’t particularly good at telling real world stories. In that regards, it was with great excitement that I approached 500 Days of Summer, which seemed to be slowly taking the world by storm (as it sits at #116 on the IMDb 250 right now). A small, independent romantic dramedy doing well is something to cheer for. But for me, it just doesn’t stack up.

The biggest epidemic in independent film continues to be quirkiness for the sake of quirkiness. Form fails to follow function, and we end up with a bunch of silly side-effects that don’t necessarily move the story or create a certain mood. The boardroom scene, for example: The speech was bad enough, but his friend’s reaction? Ten times worse. That’s a film groveling to its audience, saying, “I know this is what I’m about so far, but just in case you don’t like it, we also have some silly, stereotypical characters who will make you laugh by doing silly things!” That’s lazy, and honestly, disappointing. Throw in the whole expectations vs. reality sequence, and you’ve got it tailor-made for emotional manipulation.

Joseph Gordon-Levitt is as exciting an actor there is in my generation. Walloping this into the group with Mysterious Skin, The Lookout and his work on Third Rock from the Sun exposes his obscene range. On the other end of the spectrum is Zooey Deschanel, who continues to waste her abilities by taking the most banal of roles. If you think she’s two-dimensional in this, you probably shouldn’t watch Gigantic either. The poster girl for the modern hipster female desperately needs to outgrow her peculiarities. Someone get her a role where she plays something other than the girl that every geek wants to get with.

All this being said, I do respect the film for trying to bring a certain feel to the masses. It slipped (quite a bit, in fact), but the direction is good. Hannah Takes the Stairs will never be mainstream, and sadly neither will Chungking Express, but if the story of heartbreaks is going to get bought on Blu-ray (and maybe even get an MTV Movie Award nomination), Webb may be one of the guys to lead the way. And while it doesn’t sound like it, such a feat would deserve accolades.