2012 / Lou Ye > Nowhere do we struggle with the nature of good and evil more than when it comes to money. And in an ever-expanding Chinese economy, such dilemmas fly in the face at breakneck speed. So, it’s of little surprise that at the center of Lou Ye’s return to mainland filmmaking (( While it didn’t get a big release locally, Suzhou River is one of the better introductions to modern mainland cinema. )) is the changing subculture of China where corruption and lust intersect to ruin lives, loves and families.

2012 / Lou Ye > Nowhere do we struggle with the nature of good and evil more than when it comes to money. And in an ever-expanding Chinese economy, such dilemmas fly in the face at breakneck speed. So, it’s of little surprise that at the center of Lou Ye’s return to mainland filmmaking (( While it didn’t get a big release locally, Suzhou River is one of the better introductions to modern mainland cinema. )) is the changing subculture of China where corruption and lust intersect to ruin lives, loves and families.

At its core, Mystery is a solid thriller about infidelity, with twists that are genuinely unexpected and satisfying as long as the viewer doesn’t venture into spoiler-filled reviews. What’s impressive—as noted by the film winning best screenplay as well as best picture at the latest Asian Film Awards—is its ability to subtly shift its emphasis from a blatant and obvious (if entertaining) genre film into a social statement.

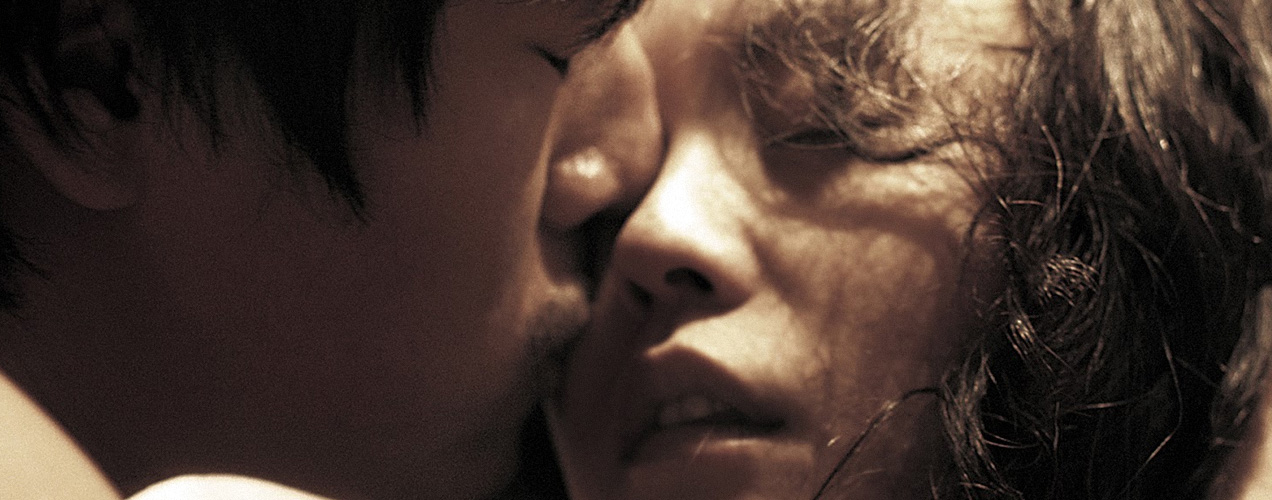

The beautiful Hao Lei (of Summer Palace fame) stars as a well-off housewife who discovers that all is not proper in her seemingly ideal household, and that her husband may or may not be playing hooky with a girl of bountiful youth. And then the wheels fall off, resulting in an analysis of a curiously amoralistic character who is so not due to nature but rather her circumstances. Surrounding her are pawns of the landscape: A mother with an adorable son whose father seems perpetually absent. A spoiled, rich boy who believes that money buys apartments, fast cars, freedom and innocence. A mother who’s lost her daughter and wants someone to pay for the crime—maybe even literally. And a husband who, sitting next to his wonderful and loving wife, can look deep into her eyes and lie. But why does he lie? Because by all counts, he seems like a good man.

All is not what it seems in this new world of fancy coffee shops and haute shopping malls. But then again, one has to wonder how much of this is China, how much of this is globalization or capitalism, how much of this is the world changing around us. Isn’t this just human nature? Will we always find a way to please that part of us that wants to act on instinct and wantonness, ravaging an otherwise content life?

This is Lou Ye’s first film to premiere in China since he received a five year ban (( Though he did take his skills to France to craft a tragic international love story starring A Prophet’s Tahar Rahim in Love and Bruises.)) for screening the sexually explicit Summer Palace, capturing a dreamlike love affair against the backdrop of Tiananmen Square, at Cannes without the government’s permission. Here, his commentary isn’t focused on the government that has become a shell of itself. Instead, it’s about the country’s progression towards a market economy where an individual’s sense of freedom comes at the expense of a widening wealth gap. It’s a world where the rich sneak past the one-child policy and daughters are buried in cash—sometimes just to keep a little face.