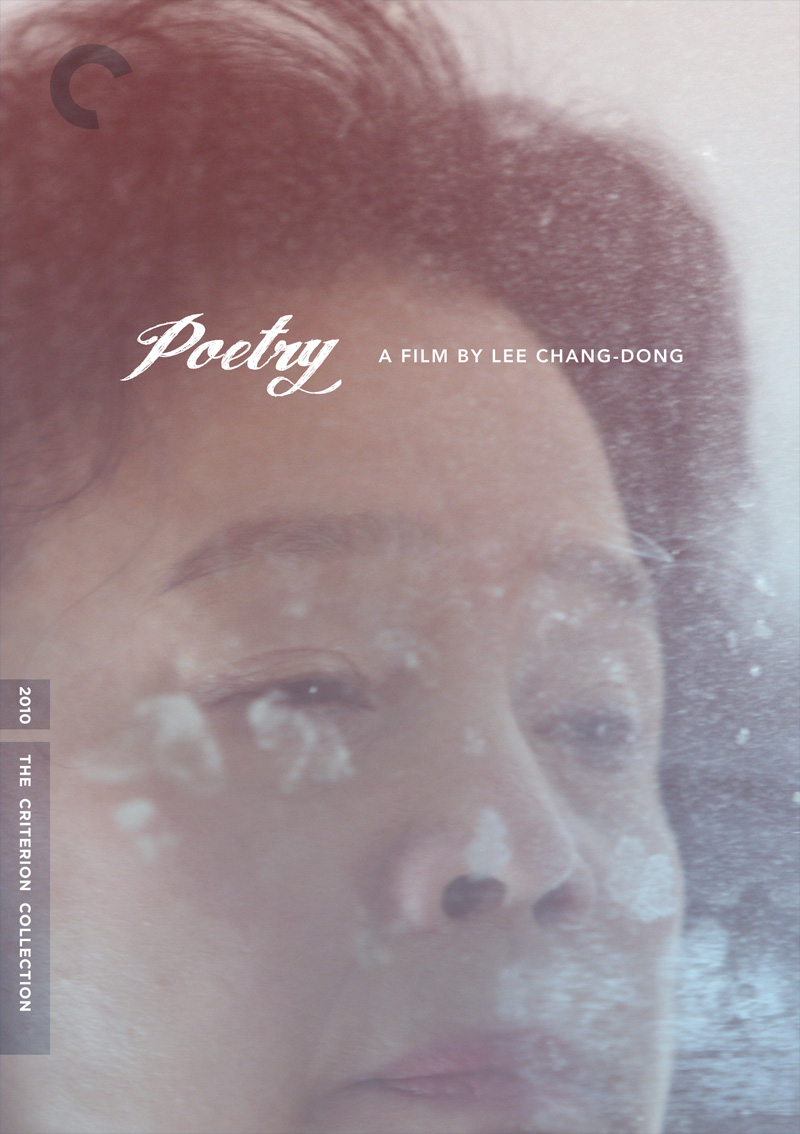

#1: Poetry by Lee Chang-dong. In the ten days leading up to the 83rd Annual Academy Awards, I listed my ten favorite films of 2010, each accompanied by a custom Criterion Collection cover inspired by Sam Smith’s Top 10 of 2010 Poster Project.

2010 / Lee Chang-dong > After a minor “hiccup” that earned Jeon Do-yeon Best Actress at Cannes for Secret Sunshine, Lee is once again at the top of his game. In three feature films (Peppermint Candy, Oasis and now Poetry), he’s covered ground on the psyche of the Korean man, love in the darkest corners of humanity and the perils of aging in modern society. His ability to so seamlessly combine the brutal strength of the human condition with a probing yet tactful eye makes him arguably the greatest of all contemporary Korean directors.

Yoon Jeong-hee’s masterful performance (the best of the year, I’d argue) guides us in Poetry. She is Mija, an older woman who seems to be losing her mind. She takes care of her moody, borderline insolent grandson while her daughter is M.I.A. She works as a part-time maid to pay the bills and stay busy. One day, she decides to enroll in a poetry class at a local community center. From the onset, we get the basic situation: The last century has been very unkind to aging parents who get left behind as their children take advantage of relocation. (The ease of remittances eases a guilty mind, but it doesn’t make up for lost time.) Lee, however, doesn’t transfer upon us the blame for Mija’s current state. In fact, his habit for developing characters who learn to control their destiny is what makes him such a fine cinematic craftsman.

Over the course of the Poetry, Mija rekindles her relationship with the cruel world she’s lived in for so long. Many of us don’t realize the daily atrocities that occur until we find ourselves in the mud with others, and Mija is no different. Lee is not a flashy director: Every scene flows into the next without extra baggage. We know what’s happening, but we’re more interested in seeing things unfold than wanting an instant resolution. The process matters. The core conflict in the film, which is best learned while viewing (and may be spoiled immediately by most reviews), creates such a moral conundrum that there would be no consensus if viewers were polled on a course of action. Whether we agree with Mija or not, we still want her to find the strength to fight for what she believes is right. Poetry is not a melodrama. It is not about the underdog coming out victorious. As Mija writes her poem, there is a solemn tone of acceptance that the world will go on—but we know this acceptance has a price, and what’s important is that we fight with her so that only she, independently, gets to judge its true value.